Three Hundred Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man — Category 5

CATEGORY 5: Ways in which it is worse to be a feminine man than it is to be a masculine man, a feminine woman, or a masculine woman. [11 items]

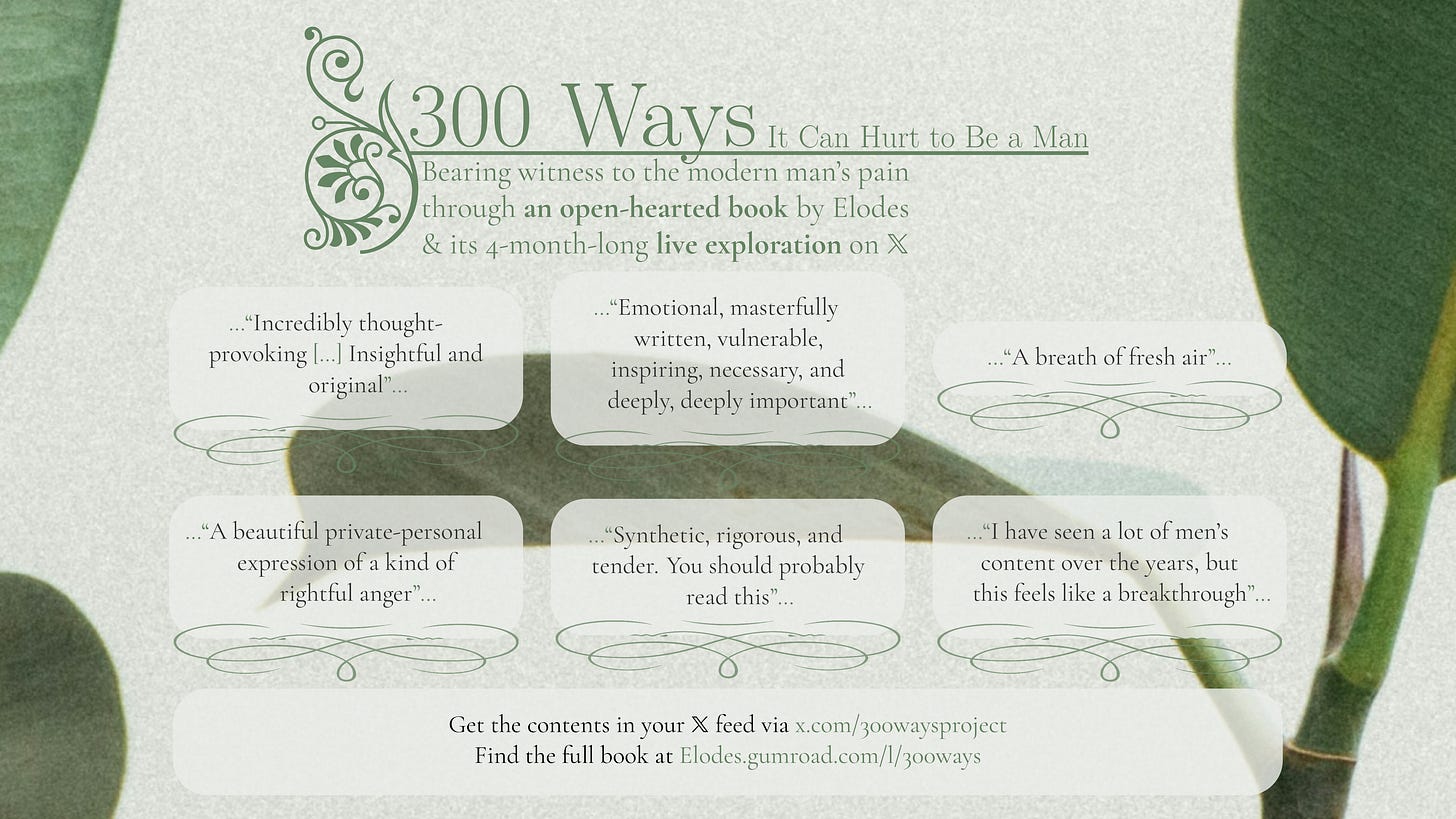

This Substack series has been made obsolete by its revised edition, 300 Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man.

Available now as a book on Gumroad: https://elodes.gumroad.com/l/300ways

Get the contents in your X feed via x.com/300waysproject

————・𖥸・————

CATEGORY 5: Ways in which it is worse to be a feminine man than it is to be a masculine man, a feminine woman, or a masculine woman. [11 items]

If we model masculine attraction as being 1) spontaneous and 2) otherwise initiated primarily by a woman’s looks or surface-level mannerisms, and we model feminine attraction as being 1) reactive and 2) initiated primarily by trust and emotional connection, then within all four combinations of gender x attraction style, men with feminine attraction have it hardest. A man who gets attracted to women just by looking at them, will be able to make his move; a woman receiving a move will be able to suss out the potential for an emotional connection; and a woman who gets attracted to men’s looks will have a field day everyday. But a man who needs to e.g. feel emotionally connected, feel trusting, perhaps feel desired, etc., will both find himself with few opportunities to be attracted enough to women to want to approach them to begin with, nor will he, being a man, be approached by women such that he may turn that into an opportunity to become attracted to her.

Even in a world where men are feminine and women are masculine at equal rates, these masculine women will find acceptance much more easily since by definition they will be able to make use of typically masculine qualities such as setting boundaries, pursuing power, being loud and unafraid, being confident, caring less about what other people think about them, prioritizing your own desires over those of other people, etc., on top of benefiting from the public’s increased sympathy towards women’s problems. Feminine men, however, will by definition find it very hard to fight for their acceptance, to speak up, and to be heard, let alone respected, since their natural inclinations will be towards agreeableness, peace-keeping, harmony-seeking, softness and quietness, a relative lack of confidence, empathy, caring more about what other people think about them, prioritizing other people’s desires over their own, and so forth. Thus if you are psychologically more like the other gender than like your own, it is far better to be female than to be male.

The old stereotypes that people are used to, are that men are masculine and women are feminine. Men nowadays are made fun of when they aren’t open-minded enough to accept, learn to live around, and respect masculine women, but women face little such mockery when they aren’t open-minded enough to accept, learn to live around, and support feminine men, and indeed are often (though not always) supported and rewarded when they complain about these men.

Women’s increased promiscuity norms make it harder for men who need an emotional connection before they feel comfortable having sex with someone, to get that space when they’re dating someone; it’s easy for a woman to think that when a men takes longer than her to want to get intimate, he’s just not into her and never will be, even when this may not be the case at all.

Much sexism that takes the form of people in some way having a lower opinion of women, directly implies corresponding lower expectations in these people, of women. A lot of women who can dash those expectations to pieces, complain about this, but women who can’t, benefit from the decreased burden that stems from not having as much expected from you, as is expected from men. Men who fail to meet the higher expectations of men, suffer from this, and would not have to face these expectations if they were women.

A related framework to the above is that gender roles for women keep them ‘in the middle’ (supporting those who do worst, oppressing those who do best) whereas gender roles for men leave men much more free to go either direction, for better and indeed for worse1. In this context, those women who complain are relatively likely to be among the ‘best’ (…whatever that means) women, since they will be most constrained by gendered expectations for women, whereas men who complain are relatively likely to be among the ‘worst’ (…whatever that means) men, since they will suffer most from gender norms that do not support them the way society’s gender roles for women support the women who are worst off. Thus, even if, say, the total amount of suffering both genders face were equal and thus in many (though perhaps not all) ways of equal importance, we’d get a situation in which women’s suffering (which is easily represented by the best women) would gain cultural attention and support dramatically more easily than men’s suffering (which is easily represented by the worst men). This dynamic makes it much harder for anyone to come out in support for the men who suffer, firstly because these men are easier to dislike, and secondly because by supporting them one risks being viewed as one of them (which in men’s situation is low-status, whereas in women’s situation, being viewed as a woman constrained by feminine gender expectations is high-status, since it means you can do better than what’s expected of you). Thus men suffer from a great lack of support relative to their suffering.

All men are often treated as though they benefit from masculine roles for men, which society perceives to be better than feminine roles for women. But ultimately what’s much more important than a role’s inherent quality (insofar as that’s a coherent concept), is how well a role suits you. To many feminine men, it does them no good at all whatever privileges come with masculine roles for men, because those aren’t roles these men were ever interested in filling anyway. Yet they are treated worse for being perceived to benefit from these roles all the same. (It’s like telling women they profit from having an increased freedom, compared to men, to fuck their way into a better life: many women are simply never going to want to take this option to begin with, and thus don’t benefit from having it and are indeed disadvantaged by being interpreted as having this option.)

It is dramatically less accepted for people we view as men to transition into being women, than it is for people we view as women to transition into being men. (This is strictly speaking not something men suffer from, since indeed those who suffer are transwomen, but it is something which those whom we view as men for as long as they are indeed pressured into maintaining that appearance, suffer from.)

We may frame masculine trauma responses as being fight and flight (both sourced in an assumed physical agency, and representing an excess in one’s boundary-probing), and feminine trauma responses as being freeze and fawn (both sourced in an assumed lack of physical agency, and representing an insufficiency in one’s boundary-holding). Then it is the case that masculine trauma responses make both men and women active in ways that are frequently still (and sometimes moreso) attractive to the other sex, and feminine trauma responses make women either quiet and inactive, or excessively people-pleasing, both of which are by society viewed as valid and indeed at times attractive ways for women to be. Feminine trauma responses in men, however, generally make them much less attractive to women. In particular, men with feminine trauma responses face the same quagmire that many lesbians face: in a pair of people, masculine in one plus feminine in the other works out well, and masculine plus masculine will often work out too, if only after a few power and role negotiations; but feminine plus feminine often means very little will happen; you end up with two people of whom neither takes the lead or initiates much. Thus of all combinations of gender x masculine/feminine trauma responses, it is often worst to be a man with feminine trauma responses. (It is worth noting that this point doesn’t quite hold up around sex: men who are traumatized into physical inaction may often fail to have any sex at all, but women who are traumatized into physical action may often push themselves too far and fail to respect their own boundaries. Neither of these is very good.)

Consider the four combinations of gender x whether or not you know what you want. Men who know what they want are in many ways in the best position, since society will generally let them pursue it. Women who know what they want are in a somewhat worse position, but much of modern society has already been shored up to allow these women to pursue their own desires too. Women who don’t know what they want will often still be able to find a positive role in supporting the desires of their partner and of others around themselves. Men who don’t know what they want, however, are in the worst position, since it is often expected, desired, and indeed required of men to know exactly what they want; a man who doesn’t really have any desires of his own and who would rather just support those around him, is often seen as weak, unattractive, uninteresting, and so forth. Thus among people who aren’t in touch with their own desires, in these ways men have it worse.

Any kind of romantic or sexual role reversal for men is less accepted than it is for women. In particular, it is much more accepted and liked by men for women to be dominant, than it is by women for men to be submissive.

For a great and detailed explanation of this framework, I highly recommend reading Baumeister’s Is There Anything Good About Men?.