Three Hundred Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man — Category 1

CATEGORY 1: Ways boys and young men are guided badly in, or taught negative things about, how to act, how to view themselves, and how to exist as men in the world. [62 items]

This Substack series has been made obsolete by its revised edition, 300 Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man.

Available now as a book on Gumroad: https://elodes.gumroad.com/l/300ways

Get the contents in your X feed via x.com/300waysproject

————・𖥸・————

CATEGORY 1: Ways boys and young men are guided badly in, or taught negative things about, how to act, how to view themselves, and how to exist as men in the world. [62 items]

Girls learn better how to socialize and interact with other people, than boys do. In this, culture fails boys.

Romance media being overwhelmingly female-coded makes it much harder for boys and young men to explore their own romanticality: what they like, what they want, what are common pitfalls in dating, relationships, and love, and so forth. (Boys get action movies instead, which… don’t exactly relate to the vast majority of men’s lives nowadays. What makes this issue worse still is that while in the past, many movies had a romantic subplot, guaranteeing boys would see at least some romance, nowadays romance and action are increasingly separated from each other.)

There are many societal programmes and projects to help girls with things that would be beneficial to them but which they for whatever reason are less likely to learn on their own (such as how to code), but practically zero societal programmes and projects to help boys with such things (such as how to communicate their emotions).

The skill of probing boundaries — that is: pushing outwards; testing the waters around one’s own agency; taking bets on other people’s happiness; and so forth — is an extremely important skill for boys to learn, but it is one which society very rarely teaches them. Indeed it is often loathe to do so.

‘Bad boy’ marketing is much more confusing than ‘good girl’ marketing. Not only is it easier to understand why other people might like good behaviour instead of bad behaviour, it is also much harder for boys to learn and understand which types of bad behaviour are appreciated by others, and which types aren’t. Moreover, bad behaviour is much harder to safely practice and experiment with so as to learn how to perform it, than good behaviour is.

The vast majority of on-screen violence in films and videogames is against men. In particular, especially brutal and bloody violence is almost solely directed at men, oftentimes nowadays as a form of comedy or levity.

Men are much more acceptable targets of slapstick humour (including rape ‘comedy’) than women are. At best, men are expected to be more resilient to this kind of humour; at worst, men are ridiculed when they are hurt by it. This tells men that even hurtful experiences must be laughed off; that their pain may not and will not be given space, consideration, and respect.

Male villain (and antihero protagonist) roles in popular media normalize villainy in men and even make it seem cool for men. This can be very confusing for boys growing up.

The relative lack of female villain roles in popular media (even as the number of female heroine roles is increasing greatly) feeds the mass narrative that women cannot be the cause of other people’s (especially men’s) suffering and never need to be stopped.

With most media centering male characters and narratives, it is much easier for young women to learn how to navigate masculine spaces, whereas for young men it is comparatively far harder to learn how to navigate feminine spaces.

Related to the above, and given moreover how often men receive stories of women experiencing sex harmfully (whether within relationships or without): Female sexuality is much less legible to men than male sexuality is to women. One example consequence from this is that when women only like to receive lust from men they’re intimate with, it often happens that young men hear “since women will only accept lust from men they love but are disgusted by lust from men they don’t, surely male lust itself is intrinsically a burden, a bad thing, something that needs to be balanced by love to be remotely OK.” A strong cultural narrative is one where women want love, men want sex, and relationships are somewhat adversarially framed as ‘deals’ where men and women exchange X amounts of sex for Y amounts of love. A society that allowed men more opportunities to learn how women actually work, would not leave them thinking their lust is inherently unenjoyable and thus undesirable, but would instead let them naturally learn that to many women, sex is simply so emotionally meaningful and intense that they could only do it with someone they really trust.

Society, including many women, tells men that to men, sex is not emotionally meaningful, that it is something men would do with anyone who’s remotely attractive. This gives many men a wrong and harmful model of their own sexuality, one which makes them underestimate and sometimes grossly neglect to notice just how emotionally involved and meaningful sex really is. Entire cultures have sprung up around teaching men how to get as much casual sex as they want, which is very harmful to the many men who find out, too late, that their answer was “none” all along.

The advice young women get from men on how to be more attractive to men, works much better than the advice young men get from women on how to be more attractive to women. (Generally speaking, women’s advice helps men optimize not for attractiveness, but rather for minimizing the risk of not upsetting the women around them. This is sometimes helpful, but it’s rarely what was requested, it’s rarely the way this advice is advertised, and it rarely centers the men’s actual needs and desires.) Finally, as it is said: “Women want only one thing, and they don’t know what it is.” Advice from women on what they find attractive in men is likely to be less accurate than advice from men on what they find attractive in women, as women themselves are often (moreso than men, as far as I can tell) surprised by the things they may, in the right contexts, find attractive, want, and enjoy.

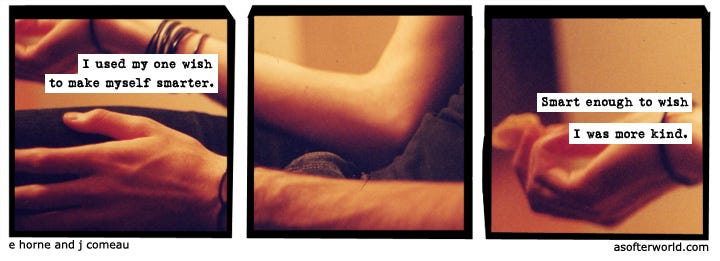

Men are taught to be intelligent; women are taught to be caring. I’d much rather be appreciated for my heart than for my mind; and I’d much rather enjoy people’s love than their respect.1

Many modern consent frameworks view consent as a binary and static thing, where boundaries are set once and then remain true, and may not be probed again, until the setter explicitly re-sets them. Moreover, they emphasize getting clear yeses and assuming no’s so long as an explicit yes has not been gained. In these ways, these frameworks fail to track reality in a number of ways, robbing men of good and fair ways to fulfill their masculine roles. Firstly, it is not the case that boundaries are static; rather, they are deeply dynamic, and what was a no five minutes ago, may be a yes now. It is important that men get to check this more often than once only, and indeed that men get to prompt women to check this for themselves, lest they forget to check. Secondly, explicitly agreeing to sex can on a felt level often seem equivalent to explicitly taking responsibility for it, which many women, given how much they value deniability, simply do not enjoy. For many women, much of the value of sex lies in being able to surrender responsibility to men they can trust with it, not to own it themselves. Thus these frameworks make it harder for men to pursue sex they otherwise could have gotten with legitimate, albeit implicit, consent. Thirdly, it is extremely common for the lack of a clear yes, and indeed what would be a clear no if the woman were pressed to be explicit about it right away, to be consensually turned into a yes anyway. For example, even in healthy, happy, long-term relationships, many women need foreplay to go from “you can kiss me” to “you can fuck me”; requiring clear yeses at all times, and especially requiring that men don’t try to turn ambiguity into yeses, would in practice render much heterosexual sex impossible, even sex that women genuinely enjoy when they do have it, and which they afterwards are happy to have had. Fourthly, many men find it difficult to own their own desires this explicitly themselves, particularly when they’ve not had much sex yet and are still in the process of growing their sexual confidence. Fifthly, some women gain much sexual confidence from seeing a man desire her so much that he’d push through all of the rejections she puts in his way; explicit consent norms make it much harder for men to successfully flirt with women who like to play this way in flirting. Sixthly, many women find a model of explicit consent deeply unsexy; thus telling men it’s rapey not to check for explicit consent, may well lead to men who want not to be rapists getting less sex, and men who are fine with being rapey, being (on the margin) more successful in getting sex. This is an awful incentive structure. Seventhly and finally, verbal consent can be given without being meant, or it can be given without an understanding of what is being consented to. In this sense it can give men a fake sense of safety, leading them to think they are treading on ice thicker than it really is. It’s easy for men who rely too strongly on explicit consent, to disconnect from the actual in-the-moment experience that their partner is having; this can lead to less embodied and less emotionally safe sex, which both men and their partners suffer from. All in all, men deserve a framework that better accounts for their role and their responsibilities, and which better integrates women’s actual, real-life sexualities.2

One great cultural trap for young women is men en masse saying they’re smarter and more knowledgeable than women, and therefore women should listen to them (lest they be wrong). A great cultural trap for young men, meanwhile, is women en masse saying they’re kinder and more prone to getting hurt than men, and therefore men should listen to them (lest they do harm). Both are very rough traps to be caught in, but the latter seems much more convincing to me. For most people it seems far easier to realize that sometimes smart people are wrong than it is to realize that sometimes causing harm is OK. (If that latter statement sounds suspect to you: I sure hope you aren’t queer, because if you were, a lot of people would feel harmed merely by seeing you kiss your partner; I hope you’ll do so anyway!)

Given that in many sexual encounters men lead and women follow, it is much easier for women to experience a wide range of different forms and styles of sex, which helps them figure out what they like, as well as how good the best sex can be. The sex that men experience, however, will often be limited in quality by their own skills, style, and courage to experiment, in leading their sexual encounters, and so forth. Thus it is harder for men to experience different kinds of sex even when they have a lot of it, limiting their space for experimentation and discovery in and around their own sexualities.

Boys aren’t taught how to groom and dress themselves, as well as girls are.

Many children spend more time with their mother than with their father, due to e.g. the father’s more time-intensive worklife, single motherhood being more common than single fatherhood, men being the primary victims of the prison system, general cultural norms around motherhood and fatherhood, and so forth. Thus boys have fewer opportunities to learn masculinity from their fathers, than girls have opportunities to learn femininity from their mothers. (Indeed, nowadays many women have taken it on themselves to actively teach their sons how to be men (whatever that means), even though they themselves often have little idea of what’s required to be a man.)

A corollary to the above point: it is often the case that teenagers, with their developing sexualities and the corresponding value of learning and following the gender roles that befit one’s own gender, will increasingly reject and indeed reverse guidance from the parent that does not share their gender, and will instead increasingly look towards the parent that does, for insight into how to behave. Unfortunately for boys, given women’s average shorter (or indeed, in more traditional middle- and high-class families, women’s lack of) workdays as well as a large proportion of school teachers being female, it is common for most guidance that boys receive as teenagers, to come from their mothers or other women, and for them to receive less guidance from their fathers or other men. Thus the advice they do get, is easily coloured by the fact that women, not being male, are relatively more likely to be viewed as primarily teaching them feminine wisdom, which at this age is oft viewed as advice to be avoided. Meanwhile, the helpful masculine wisdom that boys might receive from men, is often simply absent.

It is common for women en masse to ask men to express their feelings (“Men should be more vulnerable and open about their emotions!”), only to go “wait, I don’t like this after all” when men follow their advice. Regardless of a woman’s stance on how a man should or shouldn’t express his emotions, it can be hurtful when men are culturally told it’s safe to express them, when in fact it isn’t.

In particular, it feels very adversarial when, as a culture, women ask men to be open about their feelings (which is very new to many men), only to have little patience when they don’t know how to do this well yet. There is little understanding that when you tell a group of people who haven’t done X before, to do X, that maybe you’re gonna have to deal with them doing X inexpertly for a while.

It is moreover hurtful when women say they want men to be open about their emotions, only to then respond not just with “actually, I don’t want this,” but rather with, “Not like that.” “Not those feelings.” Open up — but not that much! Open up — but not about that! Open up — but not here, not now, not in this space, not at this time, not to me. Men are told to open up about their feelings, but when that’s sadness, people get uncomfortable; when that’s anger, people get fearful; when that’s lust, people get disgusted; when that’s feeling weak or incapable, people get impatient; and even when that’s love or enjoyment, people routinely mock men for who or what or in what way they love or enjoy. Freedom of speech is meaningless if it does not allow for wrong speech; similarly, telling men not merely to open up, but that opening up is the mature and in many ways necessary thing to do, only to reject what then comes out, is simply cruel. In particular, it can come across as a kind of fake helpfulness, as women signalling that they’re moral by saying they wish to support men, only for men to discover that this helpfulness stops the moment it requires any actual sacrifices on the part of these women. On top of the negative experience itself, this sort of thing can greatly increase men’s sense of distrust towards what looks like female kindness, and reinforces the notion that their emotions are not welcome anywhere; that they are too much for others to bear.

Broadly speaking, representation in media is such that the more a character is defined by what they do (externally, by their actions), the more likely they are to be male, whereas the more a character is defined by who they are (internally, by their emotions), the more likely they are to be female. (All other things being equal, culture likes seeing men do things and women experience things. To put it differently: it is men’s emotionality and women’s agency that culture tends to repress. In particular, horror movies — a genre which more than other genres centers around not the protagonist’s agency but simply their direct experience — are unusually likely to feature female protagonists.) But a person’s personhood resides far more in how one experiences the world than in how one affects it, and indeed someone’s lived experience — i.e. that which is there for media to resonate with — is by definition largely internal rather than external. Thus, even though men get more male characters in media (because much media is action-driven, videogames especially), many men benefit relatively little from this because these characters often fill roles that intrinsically have little to offer in terms of emotional resonance, clarity, and growth. Meanwhile, most internal character roles, roles which are driven not by actions but by thoughts and emotions and experiences, and which are thus far more ripe for resonating with people, are filled by women. (In videogames I’ve played as a hundred male serial killers, to very little personal benefit; but the stories of characters that I might relate to on a personal level, because of who they are but primarily because of the emotional depth and interiority with which their stories are told, have primarily featured women.)

The vast majority of action media (which is the majority of popular culture) stars men, but also frames their male protagonists nearly exclusively as being reactive to external crises, not problem-spotters but problem-solvers. (Superheroes never initiate improvement to the world themselves; their actions are always initiated by the antagonists’ actions.) This belies the fact that the majority of real life isn’t composed of solving the problems other people give you, of colouring correctly within well-defined lines; a better strategy for life is much more like looking at the world creatively and finding new ways to help people. Most people do not have enemies and thus needn’t be taught to fight any; however, most people do have opportunities for improving themselves and/or world, and would be best off being taught how to spot and exploit these opportunities. Much of men’s media, sadly, thus teaches a precisely wrong framing.

It’s remarkably common for films to depict male heterosexuality in entirely negative ways. Think of movies where perverse, inappropriate, or nonconsensual heterosexuality in men is used as a primary tool to mark them as villains, but which contain no positive male heterosexuality to balance this out. There is indeed very little media that positively showcases male heterosexuality in ways that go beyond a hyper-chaste “guy likes girl and maybe kisses her”-format.

Characters that are the butt of jokes (jokes played either by other characters, or by the media itself), are disproportionately male. It is still viewed as normal and acceptable for men to be depicted as dumb, to get made fun of, to get mocked, and to get denigrated, whereas this character role is much less prevalent amongst female characters; especially nowadays it is becoming vanishingly rare for media to negatively treat its female characters in this way.

As a result of the cultural norm where women complaining about men is virtuous and important, as well as the norm where many women are discouraged from speaking up positively about men (which is viewed as blocking out or even erasing female victims’ lived experiences), a culture has been created where, within the greater cultural conversation, both men and women receive overwhelmingly negative stories about men, and very few positive ones. This is extremely detrimental, firstly to men’s mental health and the way they relate to their own maleness, and secondly to the way men are treated by others, men and women alike. It’s extremely rare for most men to see a woman say positive things about men, such as that she likes men as a group, enjoys being around men, wants men, and indeed is happy to be heterosexual. As a result of all this, many men internalize the notion that nearly all men are, as a group and with only rare exceptions, unlikable, unlovable, and indeed unfuckable.

Women’s general tendency not to give honest but harsh feedback to men, spares women the risk of having to harm someone and momentarily face their pain, but makes it much harder for men to learn how they can improve in their relations to women (romantic or sexual, but also very much otherwise). (If your first thought now is that women do in fact have good reasons for acting this way, do note that we all have good reasons for acting the ways we do, but in men that’s rarely an excuse for unhelpful behaviour; women on the other hand are often given much more freedom in this.)

There is a dearth in (WEIRD) popular media for men that positively shows authentic emotionality and emotional authenticity in men.

The importance of humour in male flirting is rarely understated, for good reason; but within the context of modern dating (especially online dating), this has become quite exacerbated, since it is now much less effective (and often less accepted as well) for men to flirt without being humourous. Instead of being simply straightforwardly interested, it’s nowadays expected of men to open with some kind of joke that’s more interesting and funnier than the jokes sent by a hundred other men. This has the unfortunate side-effect of making many men feel like their being simply into someone isn’t an acceptable reason for hitting on someone; instead men have to be clever and funny, as though they have to cloak their own interest and instead must sneakily charm women into liking them before they can be open about simply liking and wanting someone.

There is much cultural knowledge around the notion that women face high beauty standards (from peers, in media, from the opposite sex, and so forth), but men are much less helped to understand that they face high confidence standards from much the same sources and to a not dissimilar degree.

Pretty much all traditional archetypical methods for men to court women (e.g. writing her poetry, showering her with gifts, treating her like a princess, persisting throughout months of rejection to prove the strength of your adoration, and so forth) are nowadays often viewed as completely inappropriate. Men cannot draw on lessons (and, for that matter, freedoms) from the past to learn how to flirt.

In contemporary culture there are almost exclusively stories of men flirting badly, and very few of men flirting well. It is far less popular to celebrate men than it is to hate on them; and it is far less normal for a woman to talk positively about a man flirting with her well than to talk negatively about a man flirting with her badly. Thus men cannot draw on lessons from the present to learn how to flirt, either.

Even when women do write about men flirting with them positively, culture as a whole is quick to clarify that just because what some man did worked on this one woman, that doesn’t mean that most women would like this (so don’t try it yourself), and it doesn’t mean that most men would know how to do that same thing well (so don’t try it yourself). Thus the few modern stories that men could draw on to learn how to flirt, are in this capacity actively disempowered by society at large.

As a whole, due to the above phenomena, many men’s overwhelming experience around romanticism is that they feel totally forbidden in, and emotionally blocked around, expressing romance, romantic desires, and romantic actions.

For men it is viewed as crass (by men, but certainly moreso by many women) to discuss their sex lives in any detail at all, whereas for women it’s a very common conversation topic. Because of this, men tend to have fewer opportunities to learn from their peers about alternative ways of doing and relating to sex. Men lack a dialogue around experimenting in sex. Given moreover that leading means taking responsibility, which often means bearing the expectation that you won’t make mistakes, the situation that many men end up in is that it’s harder for them to experiment with and explore their own sexualities.

Women are taught better how to do self-care, particularly some healthier forms of it. (Alcoholism and other forms of addiction are famously male tropes.)

On a related note: healthier lifestyles are often ‘feminized’ (i.e. connected to feminine aesthetics, marketed primarily to women, etc.) in media, making it harder for men to feel like they resonate with these healthy lifestyles.

Female masturbation and sexuality are often viewed and presented as beautiful, valuable, positive. Male sexuality is often viewed and presented as ugly, demeaning, negative. In particular, male pleasure is viewed as worthless; culturally, people don’t want to hear about it; ‘it gives men pleasure’ is never a sufficient argument for (and indeed is rarely viewed as relevant to) anything, whereas ‘it gives women pleasure’ certainly is. (Popular culture will tell you porn videos, sex robots, and fleshlights are bad; it will rarely say dildo’s, vibrators, and erotica are.) In this way, many men are told that nobody would like to see them naked and that nobody would like to witness or experience, let alone want to receive, their sexuality.

Many, many men, even moderately or sometimes very attractive men, lack a culturally-grown felt sense of feeling or being hot. It’s not so much that they view themselves as unattractive (though many men do); many men just seem to lack any sense that it would even be possible for them to be attractive. Part of this is surely that women (and men!) are taught what female attractiveness looks like, far better than men are taught what male attractiveness looks like. Thus men grow up thinking it’s really only women who could ever feel attractive, as a result of which many men miss out on the great pleasure and many benefits of feeling (and pursuing being) hot.

Culturally, women get to feel like their sexuality — that is, their pleasure, their body, their sexual actions, and so forth — has value, intrinsically as well as to those around them. Men, meanwhile, are often culturally only ever told that their sexuality corrupts value; that it devalues and degrades and, if you’re not careful, damages or destroys women. The messaging men receive (often most strongly from progressive communities) is dramatically more negative and harmful than what women are given.

It is nowadays the case that culture is often very negative about men teaching other men how to be, and live as, a man. Masculinity is viewed as bad, in many ways as the source of many evils, and to teach masculinity is viewed as teaching patriarchy, as teaching heteronormativity, as teaching cisnormativity. In particular, male communities that seek to teach men how to flirt and get with women, i.e. primarily pick-up artistry (PUA) communities, are assumed to be universally and wholly bad (because women are viewed as having so little agency that their consent is viewed as wholly disqualified whenever any part of it was earned through ‘strategies’ and ‘tricks’ as opposed to some vague undefined sense of men being ‘themselves’, whatever that means). Society seeks to disable these teachers of men, which in many ways is understandable because some of these teachers do be doing some shady shit; but when cancelling these teachers, society staunchly refuses to offer men any alternative teachers who seek to genuinely help men rather than merely wholly safeguard women. Men are in desperate need of teachers of masculinity who genuinely support them and want to see them grow and achieve their goals and dreams; but modern culture cares very little about giving men opportunities to feel supported and to grow.

PUA communities are by far the biggest cultural place that advertise themselves as teaching men how to flirt, which sucks, because many of them also teach men to value sex over connection. This is ultimately all the more harmful to men, because due to our cultural narratives around men and women, it’s harder for men to come to understand that sex won’t in itself lead them to connection, and that even though sex is what they thought they wanted so much for so long, it’s not actually The Thing. Connection changes people, and some of the most intimate connection you can have with a person is through sex; but when separated from connection, sex by itself often merely pleases, and little more. Unfortunately, men wanting sex is societally incredibly legible, whereas men wanting genuine love and connection simply isn’t. In this way, the vast majority of what society teaches men about sex, is to their disadvantage.

The overwhelming majority of heterosexual porn features physically quite forceful or violent men, which certainly some women like, but which is too extreme for most. Men can suffer from this normalization of violent male sexuality, firstly because it teaches them inaccurate ideas about what women like, secondly because it confronts them with a physically high bar for their sexual performance, and thirdly because it further enforces the idea of male sexuality as inherently dangerous and hurtful.

The lack of passionate, mutually loving sex in heterosexual porn, combined with the common presence of loving sex in lesbian porn, strengthens the harmful ideas that unlike women, men are not loved in sex and indeed men cannot love in sex. There is next to no porn that shows men receiving ‘soft love’, such as cuddling, loving kisses, and so forth, whereas women can at least, and often do, find this kind of gynephilic attitudes in lesbian porn.

The lack of porn featuring explorative sex in which men’s bodies (as opposed to merely their cocks) are actively enjoyed by women, strengthens the harmful notion that men are not desired for who they are as physically-extant people, are not desired for their bodies’ inherent beauty and desirability, only ever for how they use their bodies. It feels dehumanizing to be wanted for the things you do instead of for the things you are.

The default framing of most porn as being made not because women wanted to make it, but because women (much moreso than men) can earn a living from it, strengthens the harmful notion that male sexuality is so valueless and even harmful, that most women would need to be paid before they’d receive it.

If at this point in this list you’re wondering how it’s possible for any man at all to miss that so many women love having sex with men, consider how slut-shaming harms men, too, by silencing women who would otherwise share their heterosexual desires and their heterosexual pleasures, as well as their own positive stories of and experiences with these. Slut-shaming is moreover least common in queer cultures; thus those spaces where women are the most open and positive about their sexuality, are those that are least likely to contain heterosexual androphilic stories to begin with, relative to all other spaces.

Since porn where men are rough with women gets labeled as misogynist — literally: woman-hating — the message that men who are into rough sex receive, is that their sexuality is inherently borne of a hatred for women. Whether or not these men’s preference for rough sex is entirely conditional on their partner’s consent and pleasure, gets wholly erased in this framing. Thus many men are unjustly made to feel like vital parts of their own sexuality, parts fully capable of giving both themselves and their partners much pleasure, are intrinsically evil.

It is cruel when men are told over and over that the part of their sexuality where they enjoy rough sex, is misogynist, causing many men to downplay and often even shut down these parts of themselves, only to later find out that many women want and indeed (within e.g. the context of a monogamous relationship) need this kind of sex from them. (Similarly: to have the cultural idea that women are fragile and cannot handle the slightest hurt or offense, enforced strongly in all public domains, only to find out that a lot of women dislike being, and feel disrespected when, treated this way.) Despite the fact that there exist many women who genuinely enjoy, desire, and at times desperately want to fulfill these fantasies that here double as male fantasies, these fantasies remain (in men moreso than in women) harshly policed and invalidated by many parts of modern culture. Finally, even when women do consent, men are sometimes told this consent is sourced wholly from these women’s internalized misogyny; and of course, even when this is assumed to be the case, it is still the case that not women but men are blamed for participating in this kind of sex.

The abundance of porn made for men is in many ways a boon for men; let it not be thought that men are not grateful for it. But with cultural abundance come standardized narratives, which create firm stereotypes; thus amongst all gender and sexuality combinations, it is straight men who receive the firmest sexual stereotypes and who thus have the hardest time breaking free of these, whether that is to escape those parts of these narratives that are harmful, or merely to explore beyond them. The last person on earth to play with their own anus will be a straight man; this is to his disadvantage.

As far as I’m aware, there exists nearly no porn, nor much other media, that teaches men how to handle the masculine sexual role that they often have to fulfill: how to handle power, how to probe for boundaries, how to deal with the responsibility that women (in a feminine role) give them, how to deal with accidentally crossing their partner’s boundaries (an inherent risk in any position of relational power), and so forth. As a result of this, many men are poorly equipped to deal with many things that simply naturally pop up every now and then in sexual relationships, especially in the beginning, when they’re still getting to know their partner and their partner’s sexuality (as well as themselves and their own sexuality, both in general and specifically in relation to their partner). Meanwhile, many other men notice that they don’t know how to handle power in sex, and thus don’t dare let themselves experiment with it, which can cause them to feel (and at times, be) incapable of giving women what they want (and indeed, often, of letting themselves pursue what they want).

It is extremely common for porn made for men to get criticized, without the additional and important disclaimer that the things it gives men, namely pleasure and opportunities to explore their sexualities, are good and valuable things for men to have. Moreover, much criticism of porn that gets made for men focuses on the negative consequences for women, rather than on the negative consequences for the overwhelming majority of this porn’s audience. Thus many men feel implicitly told, over and over, that people care equally little about both their pleasure and their suffering, that on the balance even what they enjoy in perfect privacy should be considered wholly in terms of its indirect and (compared to the pleasure porn gives men) relatively slight costs to women.

There is a consistent narrative that women rarely have shallow tastes in men; men who are passed over are uniformly told it must be because there was something wrong with their personality, even though e.g. tallness is certainly something many women simply require in a sexual partner. Many women’s uneasiness with experiencing sexual attraction at least partially in the same superficial ways men do, as well as the unease many women experience when facing male suffering that they cannot instantly and easily provide a way out of, lead many women to deny some men’s very real experiences of getting rejected because of something that wasn’t their personality.

Many women complain about women being objectified in porn, which is in many ways a very true and important point; but it misses that men are frequently objectified even more, to the point that they are often not a whole person but simply a cock as far as the camera is concerned. The other parts of male bodies (as well as their expressed pleasure) are frequently viewed as so worthless that they often don’t even enter the frame, whereas women take center stage at all times. Crucially, it is not just female bodies, but also their (yes, frequently acted) desires, enthousiasm, pleasure, and character, that porn focuses on. Admittedly, the framing of much porn absolutely isn’t as gynephilic towards women as it could be, but it sure often values its women more highly than its men, who, besides their cocks, generally hold no value to it at all.

Having said that, it is of course the case that women in porn are often not framed in a way that suggests they are whole people, that they have any desires or indeed personality outside of the on-screen sex. But then, neither are men in porn. The objectification framing overwhelmingly tells men that they don’t get to view women — even women in porn, who are getting paid to do this, who they watch in total privacy for this express purpose — even temporarily as being merely vessels for their own sexual desires. This is bad, firstly, because many women genuinely like being viewed this way in sex (and not necessarily because of any kind of internalized misogyny, but because it’s simply hot to have a beloved partner be so turned on by you that they can’t think of anything except fucking you), and secondly, because when men are having sex with women, most of the time, men are already leading the sex, both physically and psychologically, meaning they’re often also trying to secure the woman’s pleasure, while also being on the lookout for the woman’s boundaries, and on top of all that they’re also trying to feel into their own desires and boundaries and pleasure, and so forth. This can be a lot to keep track of while still remaining in touch with all of it (rather than disassociating from parts of it). When people imply they want men not to relate to their partners in a primarily sexual way even during sex, they seem to misunderstand that this just isn’t how many men’s sexualities work. A genuine focus and a certain level of sexual intensity are often needed for men to lead sex, particularly due to the way men’s genitals tend to work (which, unlike many women’s, often do not change their state slowly but instead as quickly as the man’s attention does), and though most men can easily maintain this focus and intensity from sheer lust for their partner, oftentimes they can’t do much if they don’t feel like they have the freedom to focus fully on the sexual aspects of the situation, their partner, and indeed their partner’s body. For a man to play the masculine role well in sex, it’s often important that they get to frame sex in terms of their own desires, which often requires viewing one’s partner as a vessel for those desires. This is certainly not to say that all heterosexual sex must involve men playing this role; I’m strongly in favour of both men and women experimenting with both masculine and feminine roles so as to better explore and understand their own sexualities, as well as each other’s. But insofar as the man wants and indeed often has to play the masculine role, it is important that he feels free to do so. Criticism that women are objectified in media as a whole is often fair; but criticism that women are objectified in porn of all contexts, often shows a profound misunderstanding of, deeply invalidates, and actively obstructs, male masculine gynephilic sexuality.

Of course, one may make the point that even if the above is how many men relate to sex, it needn’t be; one might hold that there is a ‘better’ way for men to relate to sex, a way that incorporates more awareness and more felt spaciousness, a way that is less goal-focused and achievement-oriented and more playful, more dynamic, more sensitive to the moment as it is lived. In esoteric communities, a rare few men do teach these things. But the vast majority of discourse aimed at men that tries to make this point, makes it accusatively, guilting men for not knowing what they were never and still aren’t being taught, rather than sourcing their words in a positive desire for men to find greater enjoyment in their own sex lives.

On the topic of representation in media: men in popular films barely flirt anymore3. Neither men nor women have sexualities in the contemporary products of popular culture, which is worse for men since it means flirting with women is getting massively denormalized for us. Women have always had the option and indeed, culturally, the habit, to be, in public, deniable about being flirted with; but men have to be forward about it. The absence of clear flirting in films doesn’t just not teach men how to flirt; it teaches men not to flirt.

The greater amount of male representation in media and culture, often enforce not just stronger narratives about what’s ‘normal’ for men, but also e.g. more strongly-enforced lies which culture tells about men; a stronger absence of weaknesses men are afraid to show in public, leading to a stronger sense that weaknesses felt by the viewer do not exist in other men, and so forth.

Men are depicted in (static) visual art much less often, regardless of the artist’s gender. Male beauty, male bodies, male emotions, and male expression are all viewed as less beautiful, less deserving of being attentively and lovingly recorded.

Men are taught less to care about their aesthetics, the physical environments within which they place themselves; men are taught less to notice how their physical spaces influence them; and men are taught less how to improve these things.

I’m a big fan of Betty Martin’s Wheel of Consent framework, which emphasizes symmetrical responsibilities and legible distinctions between agent/patient and giver/receiver:

Besides that, I also like models which expand consent away from a binary “yes/no” to more multidimensional forms, such as (agreeing) “yes please!”, “yes, but only if we do it like this”, or “sure, we can try it” or (disagreeing) “I don’t want that, but thank you”, “I don’t want that right now”, or “I don’t want that, but what about this?" In general, models that leave space for uncertainty (e.g. the ‘green-orange-red’ traffic light model, where ‘orange’ means ‘dangerous, but still OK’) tend to provide more realistic nuance. In particular, I value models that emphasize the underrated value not just of setting boundaries, but also of receiving them from another person. For more of my thoughts on consent and flirting, this thread I wrote may hold some value:

For a delightful exploration of this phenomenon, I am pleased to share RS Benedict’s EVERYONE IS BEAUTIFUL AND NO ONE IS HORNY.

Hello!

I have yet to finish reading this list, and I'm sure will have words of appreciation when I do, but right now I was struck with curiosity and a glimmer of hope when on the 24th point your said that 'the stories of characters that you might relate to [...] primarily because of the emotional depth [...] with which their stories are told, have *primarily* featured women'.

What are those other (implicit minority of) such stories that feature men in this way? 🤲🏽