Three Hundred Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man — Category 2

CATEGORY 2: Ways men are forced into feminine roles and withheld from accessing valuable masculine roles. [21 items]

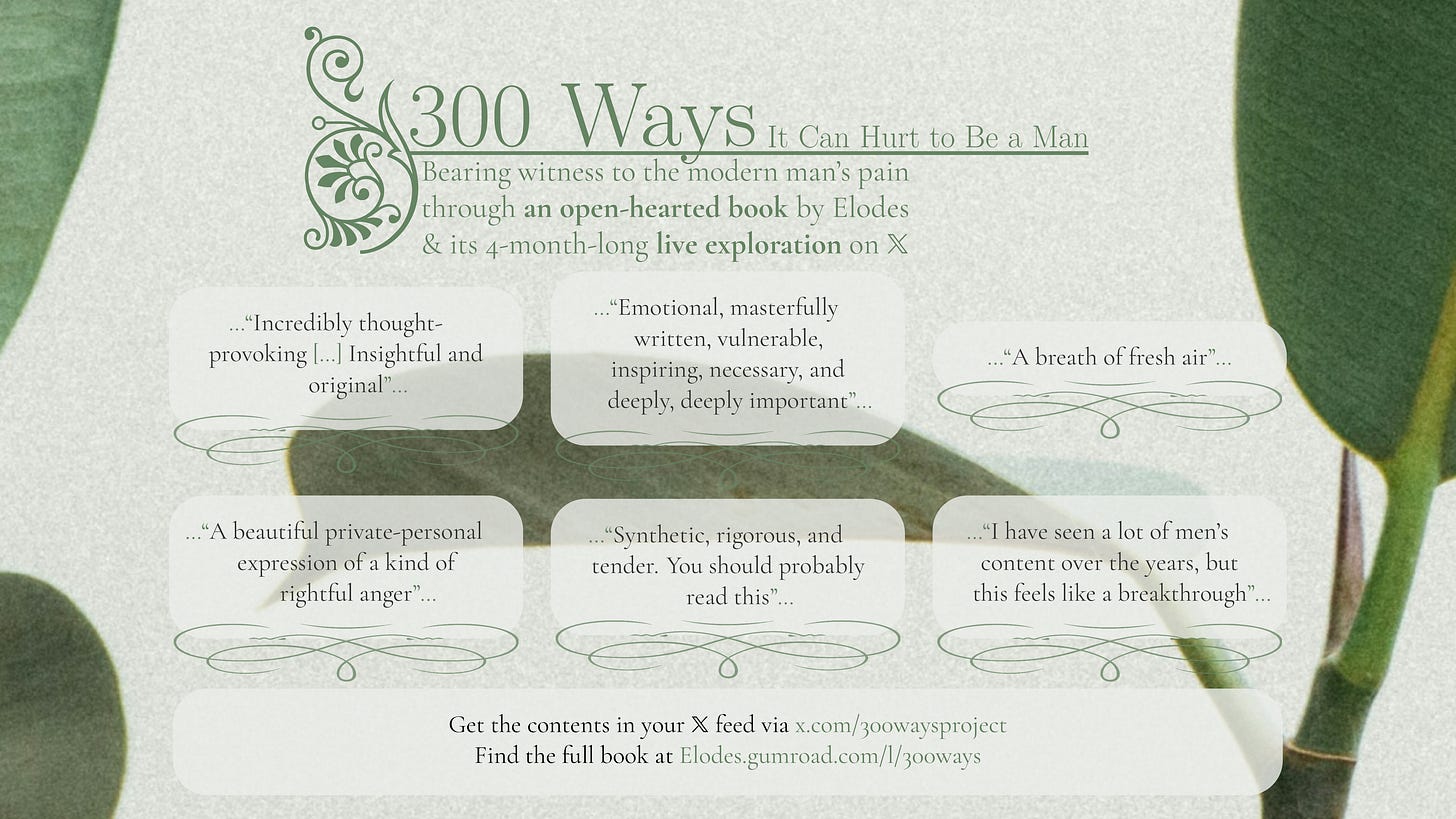

This Substack series has been made obsolete by its revised edition, 300 Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man.

Available now as a book on Gumroad: https://elodes.gumroad.com/l/300ways

Get the contents in your X feed via x.com/300waysproject

————・𖥸・————

CATEGORY 2: Ways men are forced into feminine roles and withheld from accessing valuable masculine roles. [21 items]

Boys do worse in school than girls. Indeed many of educational norms (sit still, don’t be loud, don’t question authorities, don’t fight, etc.) go directly against core masculine traits that many boys share moreso than girls. Given how powerfully formative one’s education and school experiences can be throughout the entirety of one’s life, boys are surely at a great disadvantage here when they en masse get the message that they’re dumb or incapable or not good enough, more often and more strongly than girls do.

Given how traumatic it must be for anyone to have to totally suppress many of their bodily urges and desires for eight hours a day every single weekday growing up, I would expect boys’ greater natural physical energy to cause them to be especially harmed by the norm in schools to sit still and be quiet.

Let’s posit feminine spaces as emphasizing collaboration and equality and as having a focus on multifarious and dynamic status hierarchies, and masculine spaces as emphasizing competition and clear winner-loser hierarchies. Many men enjoy situations where they must risk losing for a chance at winning; even failing over and over can be a great motivator for men, causing them to reach for heights which they’d never have sought out if they hadn’t first had their internal drive (or indeed their insecurity about their own capabilities, if that’s how you want to view it) fired up by failure. For example, many men relate to enjoying being challenged and having to earn their victories in sports or videogames, to the pleasure of being forced by repeated failure to grow into the very best version of yourself, rather than having lukewarm acceptance keep you where you are. Sadly, however, much of modern culture, for kids especially, is afraid to risk situations where anyone ever loses, and instead prefers flattening what could have been fierce and joyous competitions into seemingly supportive ‘nobody loses, everyone wins’-spaces. (Even singleplayer videogames are not safe from this call!) In particular, given men’s social roles, which relative to women’s, emphasize agency, action, and bearing the consequences of those actions yourself, it’s likely that men will face personal rejection (as opposed to simply the lack of good things) and perceived personal failure (as opposed to perceived failure of the people around oneself) more often than women. Competitive spaces can be great places for boys to learn how to deal with failure and rejection in a healthy way. It is good to give boys spaces where everyone is viewed as equal; but increasingly boys are losing spaces where they get to test themselves and those around them in a way that is at least somewhat meaningful, robbing them of valuable opportunities to grow into men capable of dealing with failure and rejection in mature and healthy ways, which is a skill the world will very much require of them as adults.

As it is said: haters gonna hate. Anyone who visibly (read: not deniably) uses power will get haters; with how many people are out there, and how different they all are, this is simply a law of life. Given that men are often expected to act more, to do more, to seek and exercise power, it is very important that men learn to deal with haters (meaning: how to bear them, as well as how to fight back) while they grow up. Many boys’ spaces organically develop norms that allow this. For instance, insults are often a common way for boys to socialize with each other: boys who don’t know each other may often start by insulting one another, allowing them to get a feel for what the other boy will let them dish out and what he will dish out himself, as well as giving both boys the opportunity to train important skills. In particular, groups of boys may often insult and bully newcomers as a kind of social game to ensure that these newcomers are here not just to deal the heat, but are also willing and capable of receiving it. After all, there is no safe training within contexts where some boys will just play the victim the moment an insult hits too hard; thus this is often tested up-front, lest new friendships are made only to soon break. Many of these spaces can be remarkably positive for men: the norm of ‘everyone insults everyone else’ greatly diminishes interpersonal hierachies and status games, helping equalize and integrate boys amongst their peers, and a good burn will earn respect (notably, not hate!) no matter who you are. Moreover, learning that you can exchange insults with friends and sometimes even cross their boundaries, without these things having to immediately and wholly destroy the friendship, can engender a great sense of trust that will serve them well as men. Finally, much conflict is much better handled directly rather than indirectly, and the implicit but strong denigration-as-play norms within many boys’ spaces certainly encourages them to work out conflicts directly, and through this learn how to do this skillfully. More and more, however, these spaces are being measured entirely in terms of their victims, with their winners going unconsidered; thus these spaces frequently go wholly unappreciated by culture, indeed even being viewed as entirely unwelcome and of solely negative value. As a result of this, these spaces are increasingly forced to be disbanded whenever noticed. In particular, many men’s online spaces have fallen victim to this growing cultural norm, with insults or play-hate earning even young boys who deserve space to learn, an instant ban. These modes of interaction are everywhere viewed as obviously toxic, even though obviously many boys naturally veer towards these spaces and keep coming back, implying they get at least some value from these spaces even when it’s online and with strangers. Nowadays, boys are left with very little space to practice these skills and to express themselves through these natural ways of male social interaction, leading them to grow into men who don’t know how to hold their boundaries, how to prod others’ boundaries, how to deal with conflict, and how to feel safe and trustful among men.

School overwhelmingly teaches submission. It takes a powerfully authoritative role over young students, routinely telling them to ignore their own desires (regarding how they’d like to use their time, their attention, their bodies, and so forth) and instead to prioritize their teachers’ desires over their own. This is worse for boys, who firstly seem much more physically active and energetic about their desires and who must thus repress them more strongly to fit norms that women fit more easily, and who secondly will as adult men (not least of all in the bedroom) be much more expected, desired, and indeed required, to know how to feel into their own desires and pursue these, rather than making them subservient to another person’s desires. Anecdotally (which admittedly may not mean much): women seem much more often to know what they want but feel incapable, in skill, support, opportunities, and so forth, of getting what they want, whereas it’s seemingly much more common for men to have everything they could want in terms of power, capabilities, sense of agency, opportunities, and so forth, only to have no clue what they want to do with these things, or indeed what they want to do in life.

Humour is an unusually important skill for boys to learn; it is one of men’s most useful skills to attract and charm women with, and it’s one of the very few deniable ways in which men get to perform the vital masculine role of probing boundaries. But an essential part of much humour is riskiness, precisely because it is in part a tool for checking where people’s boundaries lie. In modern culture, much male humour, especially risky humour, is cracked down upon, with increasingly strong norms against jokes that probe boundaries. Even many boys, who are in great need of a safe space to experiment with humour in so as to learn how to joke and troll skillfully and virtuously, nowadays see their space for making mistakes constrained by modern cultural norms. Men suffer from this greatly.

Given boys’ greater love for competition, and their greater focus on viewing the world through the lens of their own agency, it might be the case that ‘tough love’-type teaching could work well for many boys (relative to many girls); to be genuinely challenged, and to have respect withheld until success is achieved. This would be a teaching context that is mutually adversarial, where the teacher’s role is less there to support the child and more to test them. Nowadays this is becoming less and less common in schools; even telling students when they do badly that the fault might lie at least partially with them, is quickly becoming a cultural taboo. That’s too bad, since it might be just what many boys would like to receive before they’ll make a better effort.1

The male way of settling problems, namely physical conflict, is nowadays very much Not Done. The female way of settling problems, namely relational conflict, has become the cultural default. Men suffer from this cultural shift greatly, since they now lack those tools for starting and settling conflicts that are most natural for them, and are instead often forcibly conscripted into feminine conflicts instead, which many men are naturally worse at navigating.

When men want to verbally harm someone (justly or unjustly), they shame and insult that person to their face. When women want to verbally harm someone (justly or unjustly), they shame and insult that person within that person’s community. (Again, female deniability is key: if you can get a community to harm a person, you will not be asked to take responsibility for said harm yourself.) It is no coincidence that direct insults and social attacks are increasingly viewed as tasteless and unwelcome, often even being bannable offensive in both online and real-world spaces, whereas ‘supporting victims’ when they speak out about perceived harm, or even just listening to people when they share third-hand information about a person’s past actions, is becoming an iron norm in many communities. Women’s social attack strategies are being empowered, while men’s social attack strategies (which are often at less risk of growing out of control and causing disproportionate harm) are being shut down hard.

In the past, it was fairly well-understood that many people have ‘competing access needs’2, meaning that different people have different needs which are 1) valid and 2) unable to all be met within the same space. Thus, different spaces were created to meet people’s respective needs. Come modernity, however, and society has switched to thinking that a perfect space is possible, and that it is solely a matter of picking the right norms for the space. Thus the modern rules: no sexism, no racism, no discrimination, no transphobia, and so forth. This is a mistake: it intrinsically assumes that competing access needs do not exist. Now, the victims of this are not only men. For example, there absolutely exist people who spend some part of their life thinking they might be transgender, but who ultimately aren’t; however, the notion that maybe some trans-coded trait does not need to indicate transgenderness, or indeed the notion that someone might be mistaken about their being transgender, is often viewed as very stressful for transpeople (and rightly so!), who often very understandably prefer spaces where they are not constantly asked to question whether they really are trans, or whether perhaps there’s something else that is the primary cause for their experience to be the way it is. To protect transpeople, spaces that want transpeople to feel comfortable have en masse decided not to allow things that might trigger this kind of questioning in transpeople, such as stories or statistics around people who have detransitioned. To be clear: I am not saying that this is inherently wrong or bad. Transpeople deserve spaces where they aren’t constantly triggered. But when you add to this the societal notion that the perfect space exists and therefore every space should endeavor to reach for precisely that generally-agreed-upon form of perfection, what you get is that society has decided that every single space must ensure it does not make transpeople uncomfortable. Thus an entire category of people, whose questions, experiences, and existence are all just as valid as transpeople’s, but who would be enormously helped by hearing things that would make transpeople uncomfortable, are having their questions, experiences, and indeed their existence, silenced and erased. And so it goes with men too. The societal notion is that the perfect space is one where women do not feel uncomfortable, one where women feel welcome. Thus any spaces that do not meet these features, are viewed as bad (because why wouldn’t you just make your space more welcoming to women, unless you hate women?), and thus these spaces are en masse limited, banned, and destroyed. Many, many, many men’s values are getting destroyed in this process. A tremendous amount of male forms of interaction, which are often greatly important and indeed irreplaceable to men, is getting burnt to the ground; in the eyes of society, there may exist no space where these forms are allowed to exist. This co-opting and destruction of male spaces has been brutal for many men, who now cannot get important male needs met, who can often no longer socialize and exist in the ways that are most natural to them.

Men’s ways of probing boundaries, often assume people can hold boundaries, whereas women’s ways of probing boundaries, often assume people can’t, or would only want to do so in deniable ways. When these cultures clash, it is nowadays often the men who are asked to change.

On a similar note: we may frame conversational cultures as existing on an axis between “I’ll interrupt you to signal I understand you, so that you needn’t waste more of your time; you’ll interrupt me to signal you think I don’t, so that you may save me time” on one end, and “interrupting people is either a very rude way to take space from the other person, or a way to signal that the other person was taking too much space and was therefore being very rude.” As I do with all other things, let me do violence to this framework too by saying the former culture is more masculine, and the latter is more feminine. Nowadays, it’s often the case that people using the former culture’s norms are asked to adapt to the latter culture’s norms; rarely does culture ask the opposite.

We may similarly frame3 conversational cultures as existing on an axis between “correcting someone means helpfully guiding them closer to the truth” and “correcting someone means highlighting that they were wrong, which lowers them in status.” The former culture is more prevalent among men; the latter, among women. Nowadays it is often common for people using the former norm to be told to adapt to people using the latter lest they cause harm; the reverse happens rarely.

One more4 such axis. Within situations where someone has been accused of wrongdoing, we may frame two vital roles as being advocates, who actively support the victim and advocate for them, and mediators, who (perhaps in conversation with the other accused’s mediators) try to get a clear overview of the situation. Both roles are absolutely necessary. Too few mediators, and the truth is lost, with the result being that who gets punished by the community ends up being not those who did wrong, but those who cannot rouse enough people to fight for them. Too few advocates, and victims feel ignored and unsupported, feel as though they were punished for their honesty rather than loved in it during a time when they most need love, with the result being a culture where victims stop speaking out and instead suffer in silence. Here, too, I will say that mediator is a masculine role, and advocate is a feminine role. Nowadays it is becoming increasingly common for advocates to become the only role that’s allowed; mediators, through first retaining a position of attempted neutrality (which though often done imperfectly, is still often necessary for truthseeking), are increasingly viewed as aiding the accuser through their refusal to immediately and solely support victims. Meanwhile, supporters of victims who turned out to be speaking falsehoods, are rarely if ever held accountable. (Finally: this great decrease in space that mediators suffer, often means that people who get wrongly accused of wrongdoing, themselves often men, are given a far smaller chance to acquit themselves.)

Another such axis: we may view indirectness as feminine, and directness as masculine. Indirectness is at best loving, and at worst harmony-keeping with the sole purpose of avoiding conflict. Directness is at best respecting, and at worst simply damaging. It is nowadays the case that in many cultures, there is a push towards indirectness in communication, so as to avoid situations where people may be interpreted as doing harmful speech (the bad masculine style); meanwhile, harmful silence (the bad feminine style) enables much suffering itself by avoiding taking responsibility for improving other things and other people, but since it’s much harder to blame a specific person for not saying some specific thing, than it is to blame a specific person for saying some specific thing, the value of directness is getting overlooked in favour of the safety of indirectness.

A final such axis: offering criticism (tough love) is masculine, offering support and appreciation (soft love) is feminine. Criticism is nowadays becoming more and more out of style, increasingly being viewed as simply a mean thing to do (especially in e.g. a parenting context), despite the fact that to many people (and perhaps particularly to many boys and men, though certainly also to many girls and women), criticism can be a great feedback format.

It is a real shame that men don’t get to just directly express explicit sexual desire to women. (“To women”, because within gay communities, men expressing direct sexual desire to other men is rarely a problem.) I understand why this is the way it is; I understand what keeps this norm in place; and I think so much would have to change if we wanted to give men this freedom, that it just might not be worth it. But that doesn’t mean it is not a shame, and it’s messing up a lot of men. It sucks that even men who have done nothing to suggest that they would hurt women or would otherwise be unable to accept rejection, are societally told that since women frequently feel unsafe, offended, or disgusted by men’s sexual desire for them, these men do not get to be direct and honest about their sexual desires for women. Men are the victim of the fact that men being explicit about their sexual desire is itself seen as suggesting that, since they’re doing it despite common cultural norms against it, they’re probably either too clueless to know cultural stories about women’s boundaries and are therefore dangerous, or they’re intentionally rejecting those stories, which makes them even more dangerous. It’s a good norm in the sense that people who break it will reliably be people you want to legibilize as dangerous; but it’s a bad norm in the sense that this same principle holds for any sufficiently powerful norm. It’s extremely easy for “your breaking this norm alarms me” to be expressed and understood (by all parties) as “your desiring sex alarms me.” Norms like these5, where the strength of their enforcement itself enforces them even more strongly, can feel very oppressive. Many men’s sexualities are not dangerous; many men’s sexualities are not harmful; many men would never want to hurt a woman; but every single one of us is assumed to be dangerous until we prove otherwise. To many men, being told they don’t get to simply offer their sexuality to others feels like being told their sexuality is inherently undesirable, so disgusting to others that even offering it is widely viewed as an attack on the other person. So long as women are bad at setting and holding their own boundaries, I think it’s probably better that this norm continues to exist anyway, but we should not forget that it’s an extremely negative message culture sends to men.

The previous point’s model of male sexuality as inherently dangerous, persists even within many heterosexual relationships. There’s a deeply-embedded notion that men are always more powerful, such that many sexual acts that men could do to women become viewed within the framework of the man victimizing, subjugating, or otherwise demeaning the woman. (For example, a man coming onto a woman’s face is viewed as demeaning, whereas a woman squirting into a man’s face isn’t; blowjobs are viewed as more demeaning to the woman than cunnilingus is to the man; and so forth.) Much of sex, including many archetypically sex acts that are viewed as demeaning when coming from men, can be emotionally vulnerable and intimate for men. Many men have a great desire for their sexuality to be viewed as an entirely positive and wholesome thing, something that can be uncomplicatedly fully good. The physical power difference between men and women mustn’t be denied, but in many contexts, and for many men, physical force or violence is simply not a dimension on which they would ever interact with their partners on to begin with. Even when the sole relevant lenses are psychological and emotional in nature (rather than being related to physical power), men are told their sexuality is inherently dangerous, to always watch out not to hurt their partners, whereas women are told their sexuality is never dangerous. Ultimately much of modern heterosexual sex is just two people having sex with each other from a context that is largely shared; both people have desires, boundaries, insecurities, emotional attachment, and so forth; but whereas women in sex are often culturally as well as socially recognized, and helped to view themselves, as whole, emotional human beings, men very often aren’t.

Gatekeeping, i.e. the communal decision-making process of deciding who gets to be part of the community, is every bit as valuable a tool in community-crafting as rendering them more accessible is. The former is more masculine-coded (“there are winners and losers”) and indeed is more popular among men; the latter is more feminine-coded (“everyone should be included”). Despite both tools being crucial for communities to be allowed to wield (the former to shape, the latter to expand), it is the feminine tool that is becoming widely standardized, and the masculine tool that is at this point so villified that merely calling someone out for gatekeeping is often considered a winning argument, no matter whether their gatekeeping damages or indeed benefits the community.

The prevalence of dating apps has made it much harder for men to ask out women in real-world contexts, as more and more women shift to a framework of “don’t hit on me when I’m at work / at the gym / in the bar / and so forth; when I want to date, I’ll log onto my dating apps.” Meanwhile, given how unequal the attention economy is on dating apps, most men gain very little in return from these apps’ increased popularity.

Men are nowadays often asked to be more sensitive to what’s external: more sensitive to the people around them, more sensitive to the consequences of their own actions, more sensitive to the physical spaces they occupy, more sensitive to the world at large. Yet much archetypically masculine value is found primarily in men’s lack of sensitivity. For example: Women often seem more exclusive in who they will let enter their spaces, which allows them to more carefully craft positive, loving, and nourishing spaces where everyone feels safe and connected with everyone else in the group. Meanwhile, men, owing no doubt to a greater closed-offness towards the external world, seem to find it easier to exist and work together with people who they feel little love for, who they share little with, whose energies are more negative, and so forth. Men’s greater disconnection from what is around them might be a negative for them, but simultaneously allows men unique opportunities in terms of e.g. scaling up masculine spaces (such as in work) across many different kinds of people, which the world may profit from. When men are asked to be more sensitive to the world around them instead, it becomes harder for them to access masculine values and benefits that come from being more distant to the world. (Of course, with this piece I hamper men in this.)

Concept borrowed from Kelsey Piper’s excellent post introducing and defining the concept.

Framing borrowed from Alice Maz’s clear and thoughtful post on this topic, Splain It To Me.

Framing borrowed from Kelsey Piper’s great post defining these dual roles.

For an excellent post about these sorts of self-reinforcing norms, please see Duncan Sabien’s It’s Not What It Looks Like.