Three Hundred Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man — Category 3

CATEGORY 3: Ways men are forced into masculine roles and withheld from accessing valuable feminine roles. [33 items]

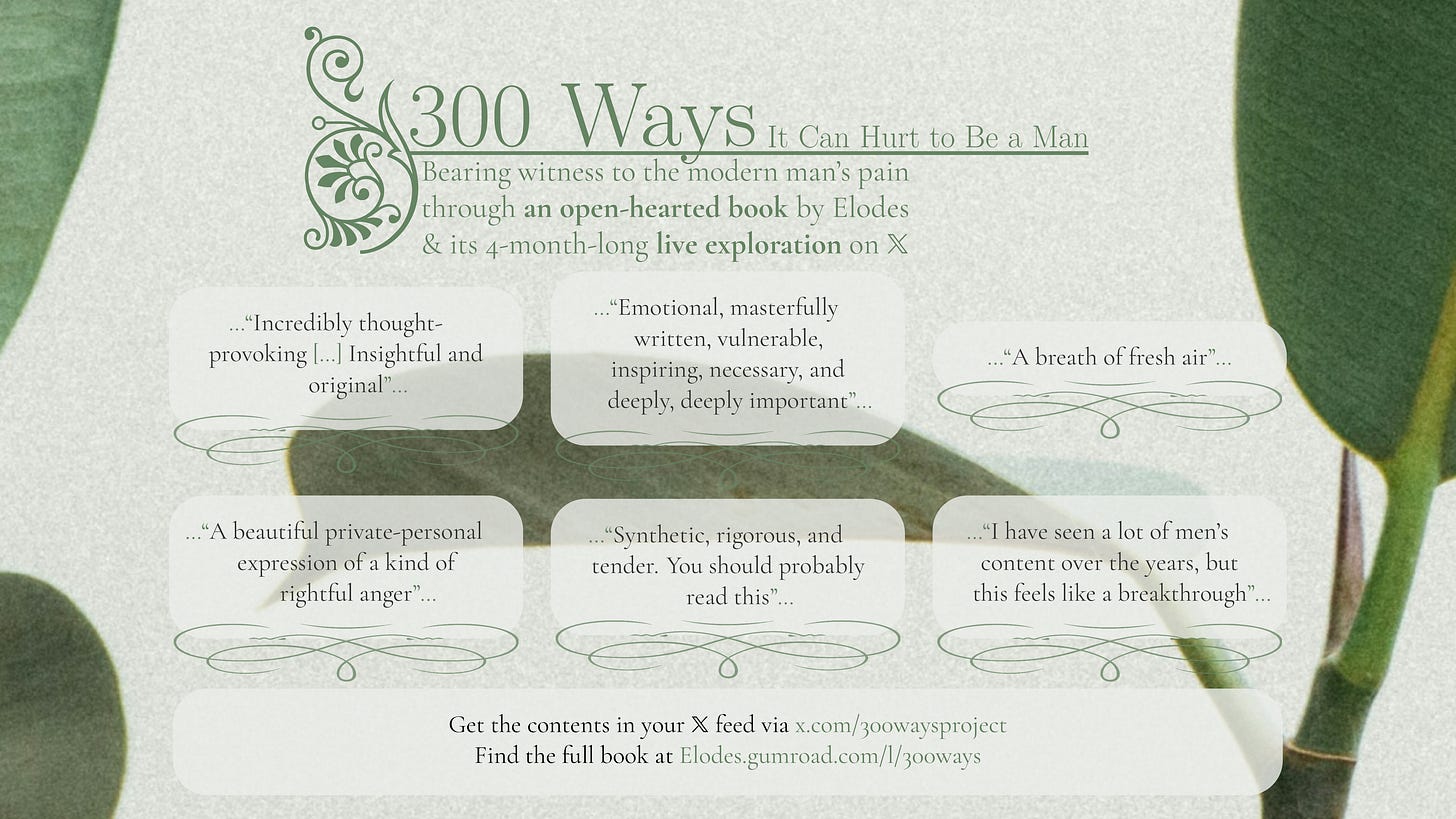

This Substack series has been made obsolete by its revised edition, 300 Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man.

Available now as a book on Gumroad: https://elodes.gumroad.com/l/300ways

Get the contents in your X feed via x.com/300waysproject

————・𖥸・————

CATEGORY 3: Ways men are forced into masculine roles and withheld from accessing valuable feminine roles. [33 items]

Boys and men get less soft love (e.g. reassurance, validation, affordances, etc. as opposed to ‘tough love’, e.g. increasing pressure, increasing stakes, withholding respect until a goal has been reached, etc.) than girls and women do.

Boys are often made fun of when they want to give soft love (to other people, to things in their physical environments, to their physical environments themselves, and so forth). For girls, meanwhile, this is a very commonly-accepted role.

In regular life, but particularly when growing up, it is much more accepted for girls to be into masculine things than it is for boys to be into feminine things.

Men, much moreso than women, are expected to work rather than stay at home to care for the family. Thus many men are distanced from what could have been much stronger bonds with their own children, bonds which many women get better opportunities to nurture.

The vast majority of men’s representation in popular fiction (movies, videogames, etc.) is of highly capable, highly confident men. This is often viewed as a fully positive advantage for men, erasing the experiences of many unconfident men who cannot at all relate to, and indeed can feel highly alienated by, these depictions of highly competent men. (Meanwhile, representation of women who are extremely competent at performing their own gender role, e.g. through being very good-looking, is widely viewed as being damaging to many women.)

Most of the representation men get in popular fiction that does not fall within the above bracket, i.e. where male protagonists are shown as weak, insecure, etc., overwhelmingly go on to center these protagonists’ journeys towards becoming strong and confident. This kind of fiction tells men that any man can become confident and strong, so long as they just do the right things. This is nearly equivalent to telling men that any weakness and vulnerability they feel are wholly their own fault (rather than culture’s, in part), and are in themselves signs of these men’s incapability and worthlessness as men.

This same genre of men’s representation in fiction, where overwhelmingly men who are weak are only featured so the fiction may go on to tell of their becoming strong, greatly strengthens the narrative that men must be confident and strong; that feeling weak and vulnerable are not also intrinsically legitimate and valid ways for men to be, the way they are for women. Thus many men further internalize the belief that their weaker and more vulnerable parts are inherently worthless and unlovable, indeed detestable, in the eyes of others.1

Women are given more freedom to not know the answer, to not know what to do, and to be uncertain, without this reflecting badly on them or causing people to lower their respect for them. In general: women have much more freedom to lack confidence without getting negatively judged for this.

Women are given more space to be emotionally sensitive.

Women are given more space to be sexy and to want to be sexy. (The equivalent for men is to be cool, and it is often remarked that to try to be cool is to not be cool; but one’s sexiness is often enhanced if one, desiring to be sexy, naturally tries to be sexy.)

Many personalities and behaviours seem more accepted in women. See also the way women’s aesthetics space is greater and more varied (in terms of self-presentation, clothing, etc.). In women it’s sweet when they’re shy, cute when they’re easily excitable about trivial things, well-behaved when they’re inoffensive, and so forth; meanwhile, shyness in men is often seen as incapability, excitedness about trivialities is seen as childishness, and inoffensiveness is seen as being boring and weak. (These traits sound abstract, but unpack themselves into many, many discrete behaviours that are more accepted in women than in men.) In particular, behaviours that require deniability are often viewed as charming in women, but cowardly in men. Finally, behaviours like adorableness, charming helplessness, explicit pull-style seductiveness, and so forth, are all wholly unavailable to men.

Women get to lack ambition (meaning here: wanting more, constantly striving for a better life, never being fully satisfied with what they have) and will be loved and accepted no less for it. Meanwhile, lacking ambition is, to many women (and men), one of the least attractive and least respectable traits a man can have.

Being open about one’s own suffering and one’s mental health issues has become increasingly high-status for women, but is still very much unfashionable for men. Even when men talk about suffering publically, e.g. to ‘spread awareness’, they will stay on a very abstract level (“oh yeah, I was depressed”, “I was just feeling bad for years”, etc.) rather than actually go into any depth and detail at all (“I couldn’t even clean my room for a month straight”, “I cried for hours every night”, etc.). Suffering is simply not liked in men; it is not something people want to see, it is not something people want to hear; men’s openness and vulnerability about their own suffering is just not something people want. (Such is society’s stance; individual people, which in practice often means “a man’s partner and nobody else”, may genuinely want a man to be open about his suffering, but even this is still uncommon.) Many men do share their pain and suffering, but where women do so openly and proudly, to their friends and on their personal social media profiles, men do it anonymously, in places where it won’t be tied to them, where it won’t even be remembered. Weakness is the thing; suffering is the thing; it is all those difficulties of living, all those vulnerable parts of ourselves, the sharing of which should form fertile soil for love and wisdom and growth; it is in many ways how we connect to others, it is what makes us human; but where women find they are rewarded in this, men often find no benefits at all, only mockery and spite.2

The above point holds not just for one’s suffering, but also for one’s incapabilities, one’s weaknesses, etc. For women, admitting to a lack of agency is encouraged, accepted, and rewarded; people view women’s lack of agency as yet another sign of their being unjustly oppressed by the world. For men, meanwhile, admitting to a lack of agency just makes people wonder what’s wrong with you, that you can’t even solve your own problems.

It feels especially hurtful that in the modern age of female emotional openness, of women en masse speaking out about their problems, that men are relentlessly told off about the ‘emotional labour’ they ‘make’ others do when they try to open up, and are primarily told to “go seek therapy” for their problems, greatly strengthening the notion that their pain is so awful for others to receive that they’d have to pay them to receive it.

In a similar vein: sadness is often seen as unacceptable in men, and being quick to cry can quickly make a man very unattractive to women. (Here I am not saying women are bad or wrong for finding easy crying in men unattractive; simply that men who are quick to cry, suffer from this.)

Being overly apologetic is often viewed as a harmless and even somewhat charming quality in women; in men it is often viewed as a deeply unattractive trait.

Much positive femininity (and there is much of it!) is in men gay-coded. (Even things like dressing well, having self-care rituals, expressing one’s own emotions, and so forth.) It should not surprise anyone that straight men experience legitimate disadvantages when they are viewed as gay. Meanwhile, though things that are lesbian-coded is an extant category, it is a far smaller one; instead most positive masculinity in women is at best fully reclaimed, and at worst tomboy-coded, which is a generally well-accepted category of woman nowadays and one that focuses much more on the behaviour itself (and is therefore at less risk of inaccurately describing the tomboy-coded women in question), than gay-codedness, which focuses not on the acts in question, but on an assumed underlying sexuality.

For men, it is not a generally accepted cultural role to want to be a ‘househusband’ who primarily cares for his family directly instead of working to earn money. To wit: ‘househusband’ isn’t a word.

For men, it is not a generally accepted cultural role to want to primarily support their wife in her career. Men who do not have ambitions for themselves are viewed as lazy, unworthy, unproductive, and unattractive. It is a greater, more fearsome challenge to reach greatness oneself than to try and help others be great (in part because it is easier to accept supporting someone else only to still have them fail, than to have failed oneself). In having only the more difficult option available to them, men have it harder.

There’s a sense that even moderately attractive women essentially get to simply love men into marrying them. Men have far less freedom to just love someone so much that they are through this rendered good enough. The role which men are expected to fulfill, is to please not their partner, but the world at large, which is much more difficult and much less within one’s own control. To frame this differently: When women fantasize (or indeed write erotica) about men, they imagine men who are intelligent, rich, famous, highly skillful, charming, ambitious, and so forth. When men fantasize about women, they imagine women who desire and love them.

OK, and who have big tiddies. Sue us! Let me take this moment to note that there seems to be a common misconception amongst women that the things men watch in porn are also the things they desire romantically, since romantically is how many women relate to much of their porn. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Men overwhelmingly consume porn just to get their nut out, and specifically to do this while feeling as little as possible, since for many men who watch porn, to be reminded of how much they need to feel loved, and aren’t, is to feel hurt, which might still be OK if they could e.g. cry that hurt out or talk to friends about it, but often they can’t. (For this same reason, many men rarely give themselves the space to properly fantasize.) Because of this, men as a whole are often thought of as being less interested in love and being loved, but the tales men tell when their names and faces are shrouded, tell a very different story. A man’s intense desire for love can often feel very vulnerable to him; it tends not to be something men feel they can share with many people at all.

Women are given more space to be shy without it reflecting negatively on them.

The cultural role of men as initiators (in any context whatsoever) greatly benefits shy women; it is less necessary to learn to approach others, and how to do so, when others approach you. Shy men may benefit from no such advantages.

Women are given more space to be insecure. Insecurity in women is accepted as a valid way for a woman to exist. Insecurity in men on the other hand is often viewed as deeply unattractive, and burdensome to those around them, even dangerous.

A woman who demands that a space change so as to make her feel more welcome, will in many cases be taken seriously. A man who demands this of a space will be laughed out of the room.

There is greater cultural pressure on men to be funny and to be interesting. It’s much harder for a man than for a woman to become liked solely by laughing at other people’s jokes or listening to other people’s stories.

Being excessively and effusively positive/joyful/happiness-expressive is, in men, often viewed and felt negatively, particularly by women. It is not impossible for a man to pull this off, but it is certainly much easier for women to be better liked in such a way. A woman who smiles all the time is often cute; a man who smiles all the time is often suspicious. A woman who emotes a lot or sends lots of emoji’s is often viewed as expressive in a positive way (transparent, open, etc.); a man who does these things is often viewed as expressive in a negative way (pushy, loud, etc.). A woman squealing, excitedly yelling, and going all-caps, full-exclamation-marks, is often viewed as charmingly upbeat; a man who behaves this way is often viewed as way too extra, and probably gay. This reinforces the felt sense in many men that their joy, their love, and their happiness, are things that make them less attractive to others.

Women may wear masculine clothing, but men may not wear feminine clothing.

Men in general suffer from feeling like they always have to perform, are always judged for their achievements, and are worthless without these. Even in sex, the cultural conversation frames men’s value in terms of how they perform, as opposed to women, who in the cultural narrative are framed as offering enjoyment and value simply through existing. There are almost no spaces, especially in sex, where men can let go, give up their responsibilities, and surrender to a greater context.

Male attractiveness is very active; men have to actively make themselves attractive through their behaviour, and cannot know for sure beforehand if it’ll go well. Female attractiveness is much more passive; thus attractive women can safely rely on their being attractive.

It is often not good to be excessively, self-effacingly agreeable (or ‘people-pleasing’). Having said that, a woman who endeavours to please the men around her, will often indeed please them, whereas a man who endeavours to please the women around him, will more often fail at this, because many women (for better and for worse) simply don’t like a man who tries hard to please them.

There is extremely disproportionately little support available (both socially and epistemically) for men who have suffered from sexual assault, relative to the support that exists for female victims of sexual assault. Men’s roles in sex, and their relationship to their own sexuality, are often categorically different from women’s, so it’s important that these men be given specific support and guidance, sourced from a context which understands men’s unique psychologies and experiences. Currently, compared to women, men are severely unsupported in this.

I have reliably found Terrence Malick’s ethereal films to feature some of the most beautiful and humanizing depictions of men that I’ve come across. Highlights include The Tree of Life and A Hidden Life, though much of his oeuvre is worthwhile.

For a thoughtful and incisive exploration of the differences in how women and men express and talk about their own suffering, see Hotel Concierge’s We Need To Sing About Mental Health.