Three Hundred Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man — Category 7.1

CATEGORY 7.1: Ways in which men’s ways of relating to everything, such as the self, the world, and life, can be hurtful. [20 items]

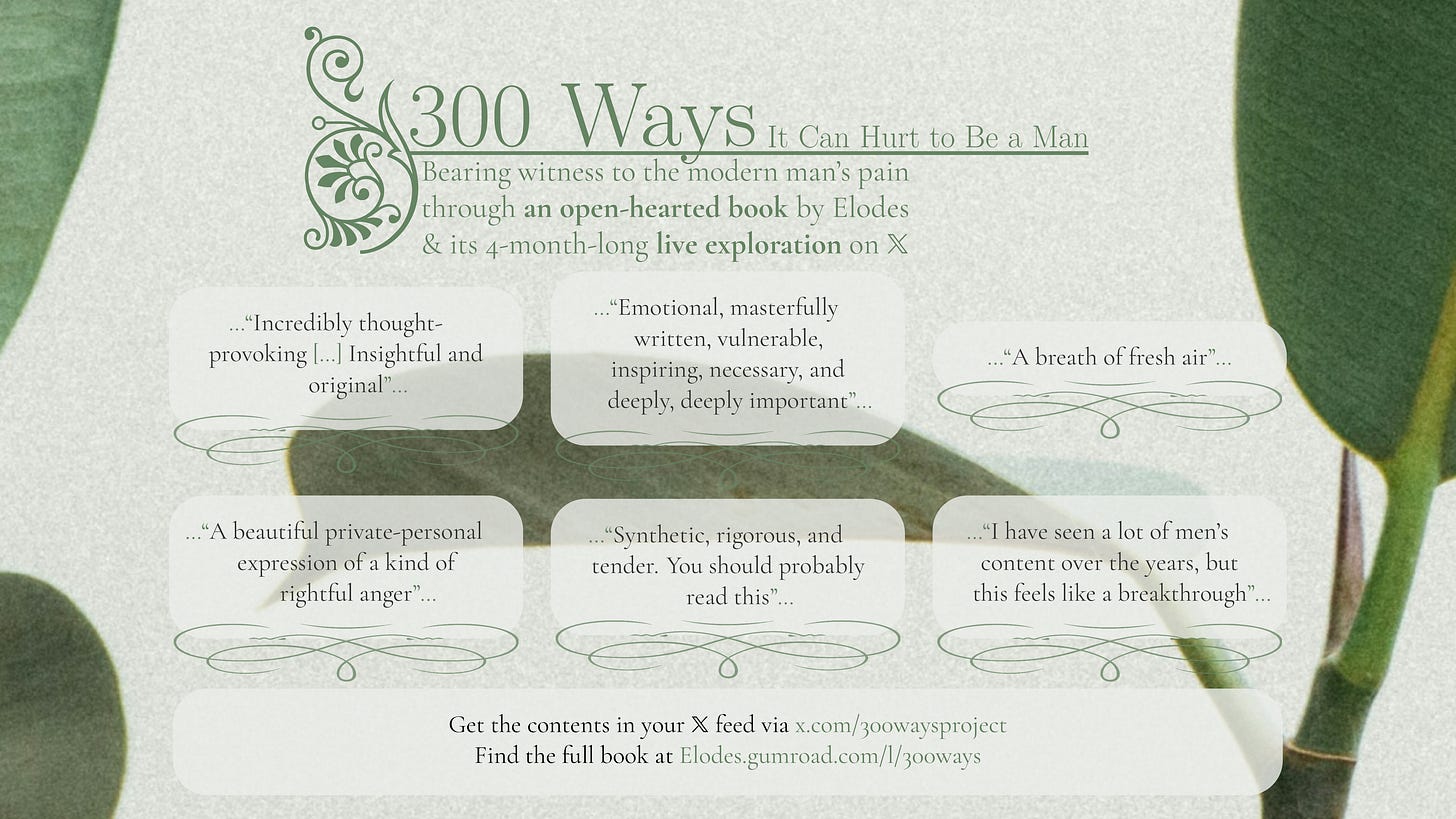

This Substack series has been made obsolete by its revised edition, 300 Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man.

Available now as a book on Gumroad: https://elodes.gumroad.com/l/300ways

Get the contents in your X feed via x.com/300waysproject

————・𖥸・————

CATEGORY 7.1: Ways in which men’s ways of relating to everything, such as the self, the world, and life, can be hurtful. [20 items]

Men are taught agency so as to turn what they want into what they have; women are taught gratitude so as to turn what they have into what they want. (An example: Products for men are marketed around what they will let men achieve; products for women are marketed around letting go and enjoying the moment more.) Agency is absolutely nice to have in many cases, but ultimately almost all of us are overwhelmingly at the whims of forces much greater than us; we all suffer from larger systems, relational problems, forms of oppression, status hierarchies, disease, wars, natural disasters, betrayals, disappointments, the aging of our bodies, the deterioration of our minds, and all the vicissitudes of fate. Within the grand context of life, we are ultimately not in control. When agency is the strategy you are taught, you will keep struggling against that which you cannot change, which is in truth most things; only with gratitude can we accept the things that ultimately happen to all of us. (To wit: Buddhist monks, who maximize on gratitude and acceptance, are happier even than billionaires, who maximize on agency and power.) Paradoxically, then, women are by culture given a far greater ability to actually deal with life, than men are.

In general, advice for men is focused around their individual agency, which can be useful; but there is a different and, I think, overall much greater type of power in the way advice for women is focused around the agency of those around them. The latter is slower, but ultimately seems to get women as a group what they want without future women even having to ask for it. Less speed but higher acceleration ultimately (and in many ways, already now) means more power for women than for men.

A consequence of the previous point is that men who have problems, get told that they have to change, and conclude this is because they weren’t good enough in the first place. Meanwhile, women more often get told that the world has to change, which makes it much easier to feel confident in one’s own worth. Women despair because the world isn’t good enough for them; men despair because they are not good enough for the world. Neither position is great here, but women’s seems easier to bear.

Women are gaining much ground in being respected as being agents, without giving up much in terms of being respected as being victims; meanwhile for men it is becoming harder to be respected as agents, and it has always been very hard for men to be respected as being victims.

A strange truth, but a truth nonetheless, is that it is often simply hard to be a person. It is hard to initiate, to take action, to have desires, to take risks, to follow your dreams, to stand for something, to set boundaries, to wield power, to make choices and to take responsibility for them. These things are in many ways necessary, but they are also difficult. For better and for worse, women are in many areas of life given more social and cultural freedom to not ‘be people,’ to denounce and especially to externalize the choices, the power, the risks, and the responsibilities that come with life. It is far more accepted for women to give these things up and instead surrender to the contexts and roles that are created for them, than it is for men. There is a great simplicity, and a great emotional freedom in the absence of responsibility, indeed in the absence of power, which come with surrendering in this way to what’s external to oneself. (Indeed, a very common source of unnecessary harm and strife, is when people try to control that which they can’t.) In particular, it is often easier to have suffered oneself than to bear responsibility for having made others suffer. The self-sacrificial, people-pleasing, power-surrendering role is in many ways the easier road, and women may walk it much more easily than men.

Women are told they are the victims of their own unhappiness; men are told they are the perpetrators of their own unhappiness. The latter framing pre-supposes, and indeed suggests, self-distrust and self-destruction. It is in many ways a more harmful framing to be taught, than the framing women receive, is.

Women seem much more in touch with their bodies (that is to say, their physicalized emotions; for the body is where our very nature, which is emotional, is felt, and expresses itself), than men. Insofar as this is indeed the case, I can barely overstate how bad this is for men. The more disassociated you are from your own (embodied) emotions, the less you will be able to live life in a way that feels good, that feels true to who you are as a person; and the less you will be able to actually notice and enjoy such a life. If one’s emotions, naturally, define and shape the path to happiness (for what else could?), then men, who are much less in touch with their own bodies and emotions, face in this a categorical disadvantage when it comes to pursuing their own happiness. (There are many possible reasons for why women might be more in touch with their own bodies than men, not least of which is women’s menstruation cycle regularly and reliably drawing attention to how strongly one’s direct experience depends on one’s physical state. Men’s bodies meanwhile only directly draw their attention when they get turned on; I think most men feel most physically in touch with themselves almost solely when they are aroused, and even then the focus is often fully on their genitals and their sexuality rather than on their entire body and psyche. Similarly, many women touch and feel pleasure from their entire body when masturbating, but you’ll be hard-pressed to find a man who is sufficiently in touch with his own body to like to please any part of himself other than his genitals when masturbating. (This lack of embodiment extends to more than just physical bodyparts; men as a group are famously quiet during masturbation and sex, whereas women famously aren’t.)

Due to men’s generally inferior ability to (crucially: physically) introspect on and communicate their own emotional state, as well as men’s (and women’s) greater social and cultural incentives to care for women than vice versa, women’s problems are very likely to long remain much more legible to society (and indeed to themselves) than men’s. Epistemically speaking, people will perceive their greater society as being much worse for women relative to how bad it is for men, then is legitimate.

To add to the notion that men feel less embodied than women: anecdotally, many men seem extremely divorced from their ability to notice the vibes around them: of text, of art, of one’s physical surroundings, and crucially, of other people, and indeed of themselves too. Women by and large seem much more skilled at this. (I sometimes wonder if, for example, men’s relative focus on looks rather than interpersonal energy, when it comes to feeling attracted to someone, is indeed its own genuine, inherently valid form of sexuality, after all a proper half of human sexuality, or if it is rather due to the fact that many men get low-key traumatized out of noticing anything but the most superficial features of their direct lived experiences, both internal and external.) Being unable to notice subtleties in one’s own experience is likely better insofar as one’s own experience is worse; the fact that many men seem to have learned to disassociate from their experience to such a large extent relative to many women, does not suggest positive conclusions about what it’s like to grow up and live as a man.

There’s a sense in which many male expressions of agency, including e.g. much of archetypical male sexuality (hurried, impatient, desperate, excessively goal-focused instead of pleasure-guided, insensitive to what is external to oneself, etc.), may be viewed as expressions of attachment trauma or deep heartbreak (in the more general sense of the word): coping mechanisms for men whose very bodies carry their fear that they will never be given that which they do not actively take for themselves. Many men’s agency and sexuality are the agency and sexuality of people who secretly believe they don’t deserve or won’t just be gifted what they’re pursuing, who thus try to maximally exploit whatever space they are given to gain it, since any such space must surely be a mistake on the part of the giver and so must be taken advantage of before the giver realizes that of course these men don’t deserve, and of course they don’t want to give to them, what they’re pursuing. Much of men’s agency comes less from confidence, and more from desperate need and a deep-seated fear that they are at their core unlovable. Of course when men don’t pursue love before they pursue other things, maybe that’s because they were taught that they are inherently unlovable and thus concluded that pursuing love first is nonsensical to begin with.

On that note: much of modern culture, similarly trust-traumatized, likes to ask: “Who needs trust when you have agency?” But an equally important question is: “Who needs agency when you have trust?” Many women, for better and for worse, seem better able to keep trusting (or indeed worse able to stop trusting) than many men, who internalize everything that happens to them so they need not depend on anyone. It’s a lonely life, permeated with a disconnectedness from those around oneself. Men are often envied for their agency, but this misses that it is often borne from pain, and can easily cause men to destroy what with more trust they might have gained and preserved. Even on a purely embodied level, there are many ways in which agency is harmful to oneself: a constant wariness & readiness to act, tensions embedded and stresses kept alive within one’s muscles, vs. a physical ease, a deep relaxed trust in one’s own safety, indeed an embodied non-doing.

Nowadays, there is culturally a far greater focus (for people as well as for corporations) on minimizing harm, rather than on maximizing net benefit. People and corporations are evaluated on the worst things they do, rather than on the net sum of all they’ve done. Among the many downsides of this framework is the fact that it privileges inaction over action; in this, it disproportionately disadvantages men.

It often feels like, while it is certainly not easy to be a woman, it is relatively simple, since various traits come with clear tradeoffs. In traditional cultures in particular, women are simply liked more the more they maximize on archetypically feminine traits like beauty, fashionability, agreeableness, quietness, attentiveness, lovingness, social skills, harmony-keepingness, and so forth, so the question for women is moderately cleanly the question of how they want to balance being liked by other people vs. having freedom from fulfilling these roles (whenever that is what they want). (This ignores much nuance, of course, such as the way increased beauty can often cause increased intrafeminine competition and jealousy.) On top of that, female beauty standards are relatively uniform, so it’s easy to know what to shoot for. For men, the landscape seems much more confusing, since very little can simply be maximized on, and instead the job for men is to find the right balance. Men must be confident but not arrogant; emotionally robust but not distant; vulnerable but not burdensome; hard-working but not a workaholic; forward but not creepy; well-dressed but not too well-dressed; standing up for oneself but not being hot-headed; being interesting to women but not mansplaining; respecting and listening to women but not putting them on a pedestal; firm but not hurtful; leading but not dominating; loving but not intense; lustful but not sex-crazed; and so forth. It can be very hard as a man to learn how to be and how to act, because for a long time it’s not made clear at all that every single thing that society asks of them is in fact hugely situational, and of course even once that becomes clear, the outcome is a more confusing, more subtle, more contextual system of norms and rules and expectations than it seems like women are generally faced with.

For whatever reason, it is often the case that men optimize for legible metrics of success and happiness (perhaps because they’re traumatized out of noticing more illegible metrics? Likely there are other reasons as well, though), like how much money they make, how much they can benchpress, etc. (Not unrelated: the famed videogame genre that is ‘numbers going up’ tends to attract many more men than women, even relative to videogames’ usual audience gender makeup.) Women, meanwhile, tend to optimize more for less legible metrics, like how they feel (physically and emotionally) in their bodies, the way their physical environment impacts them, ensuring their lives contain many small things that add meaning and happiness, the way they make other people feel and vice versa, and so forth. Though these metrics are less legible and dramatically less quantifiable, they are also likely much more important for a person’s happiness, and it’s clear women know better how to appreciate and pursue them.

To add to the above framing: not only are women at an advantage here by knowing to prioritize what cannot be measured over what can; it is moreover the case that statistics will, of course, primarily measure those things that are easier to measure. Thus even in a world where women are doing better on metrics they optimize for, and men are doing better on metrics they optimize for, and even if men are doing worse overall, you would still have a situation where the majority of statistical research will conclude men are receiving better outcomes in life.

It is often much harder to ‘take’ (the archetypically masculine role, and indeed what is often asked of men) than to ‘give’; after all, it’s safer and more controllable to risk your own happiness, than to risk that of others. (Perhaps relevant: there are more women with a submission kink than there are men with a dominance kink. One of these roles is harder to fulfill than the other, and it’s not submission.)

Broadly speaking, men seek respect, and women seek love. Both are very valuable; but as far as I can tell, there are many more unhappy respected people, than there are unhappy loved ones. Seeking love seems the wiser attitude to have, and men, for whatever reason, are more distracted and more disconnected from this goal, than women are.

Since it is only power which reveals to people who they ‘truly’ are (that is, who they are when they have power), people whom power would reveal as being e.g. careless or evil, are at less risk of discovering and confronting this in themselves insofar as they are less likely to be in a position of power. Insofar as women are indeed given less power than men, weak and bad women are by this advantaged over weak and bad men.

It is often much harder to live for oneself than it is to live for other people. For many people it is easier to do things for others than for oneself; easier to forgive others’ imperfections than to forgive one’s own; easier to give gifts to others instead of to oneself; easier to listen to others with love and care than to listen to oneself; easier to stand up for others than to stand up for oneself; and so forth. In general, culture demands of women that they support others, and of men that they support themselves. The former role seems much easier.

Growing up, given how often men’s emotions are viewed as too much, as unmanly, as too intense, as inappropriate; and given how little loving touch and soft love men receive from anyone at all; and given how many men nowadays feel most, if not solely, connected to their bodies through their own genitals; many men eventually learn that the only space where they may embody and express their emotions, as well as the only space where they may receive love and intimacy, as well as the only space where they get to physically feel into what it is to be alive as a human being, as a human body — is sex. Of course men end up wanting ‘only sex’! To so many men, sex is so much more than sex; it’s the only space where they may be, and feel, human. So when men are told they don’t get to express wanting sex, when they are nearly wholly forbidden from pursuing sex, and when they are given no guidance nor space for exploring both masculine and feminine roles in sex, many men ultimately see their final chance at feeling like a full, worthwhile, human, wanted, loving, and loved person, get shut down completely, and are in this way finally closed off from so much of the grand glory that is human love and life.