Three Hundred Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man — Category 7.3

CATEGORY 7.3: Ways in which men’s ways of relating to their own (perceived lack of) inherent lovability, can be hurtful. [26 items]

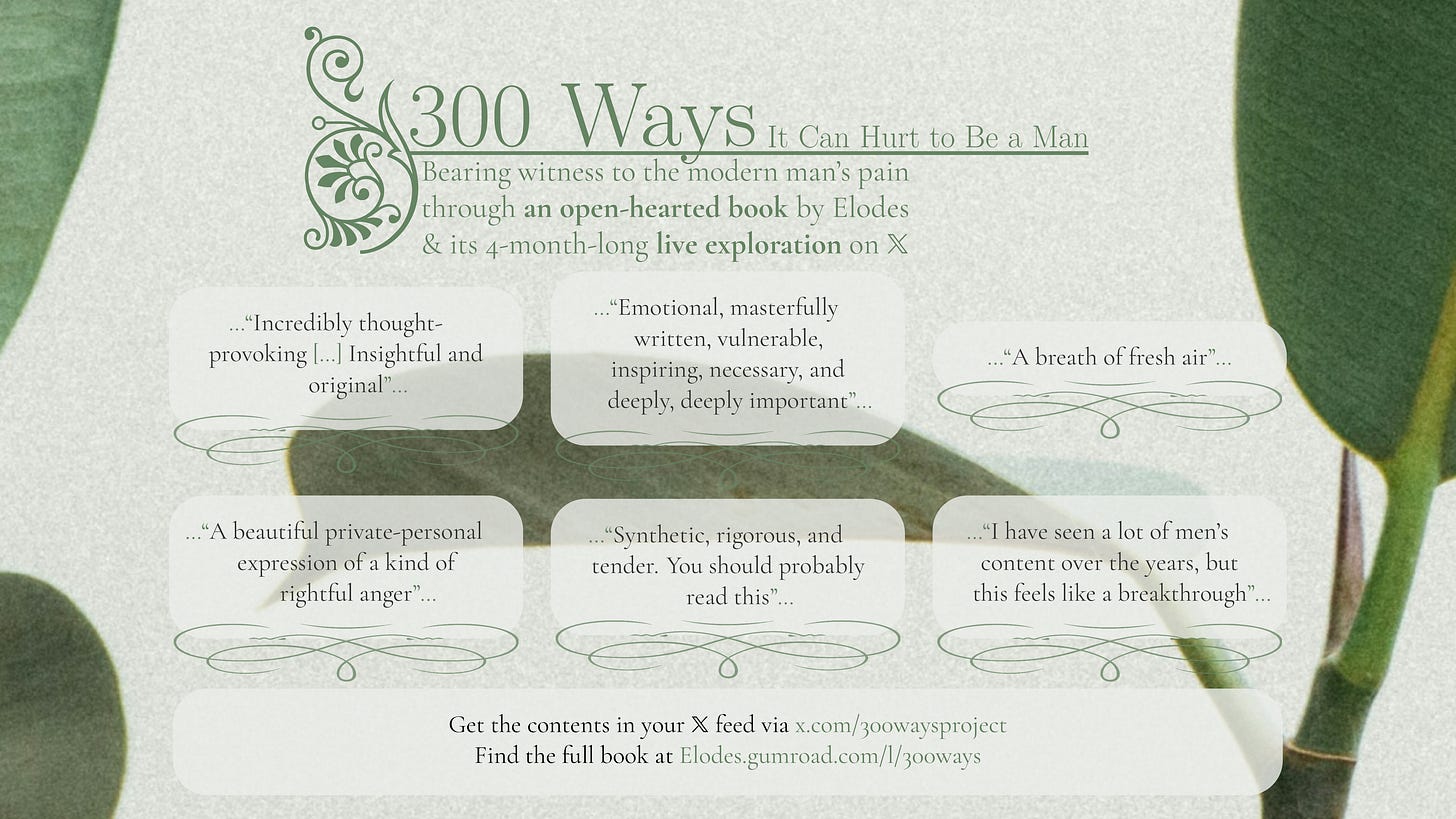

This Substack series has been made obsolete by its revised edition, 300 Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man.

Available now as a book on Gumroad: https://elodes.gumroad.com/l/300ways

Get the contents in your X feed via x.com/300waysproject

————・𖥸・————

CATEGORY 7.3: Ways in which men’s ways of relating to their own (perceived lack of) inherent lovability, can be hurtful. [26 items]

It is far more common for men to hear negative stories about men in both the news and in fiction, where men are evil, harming women, etc., than it is for women to hear negative stories about women, either in the news or in fiction, where it is they who are evil, harming men, etc. Many men I know have suffered from this greatly, and I can barely bear to imagine how this might impact boys growing up in contemporary culture. It’s particularly galling given how many women seem to understand very well how important positive representation is, and how profoundly hurtful negative representation can be.

Girls get told by society that they’re not pretty or hot enough to be loved; boys get told that they’re not confident, courageous, or ambitious enough to be loved. Men are made insecure not about their bodies, but about their actual personalities. They’re told that to be worthy of love they cannot simply change the way they look; they must become an altogether different person than who they currently are. Men are told that when they fail to receive love, it is because they, being who they are as people rather than as bodies, simply are inherently unworthy of other people’s love, and indeed that other people actively perceive them as not being worthy of their love.

Women can get loving casual touch (e.g. hugs, cuddles, etc.) much more easily than men. In this, many men severely miss the extremely valuable felt experience of being loved, being safe, being among people they can trust, and so forth.

Men get dramatically fewer compliments than women. As a result of this, many men feel less valuable, and indeed less valued, across many areas within their sense of self.

To put it very broadly, ignoring much nuance and defining ‘attractiveness’ as ‘what initially catches the eye or sparks crushes’: looks are more important than personality when it comes to female attractiveness, whereas personality is more important than looks in male attractiveness. To put it differently: women have to look hot ‘no matter who they are’, whereas men have to have a hot personality ‘no matter what they look like.’ To me, the latter feels much more constricting; it reinforces the view that the weaker, worse parts of my personality are genuinely unlovable and actively impede my attractiveness in other people’s eyes. I want the freedom to be myself fully and still be loved in that; but as a man, this is harder for me to get. There is a sense that when it comes to who we are as people (as opposed to ‘as bodies’), women can still be perfectly lovable within their weaknesses, whereas men are only ever loved for their strengths. Another way to frame this would be “women must be pretty, men must be confident.” All in all, it is surely much worse to be found unattractive for your personality, than for your looks.

Men enjoy helping women (through teaching, tutoring, explaining, etc.) more than women enjoy helping men. (For instance, it’s much easier to pull off a “I don’t know anyone here, can you introduce me?” / “I don’t know anything about this, can you teach me?” when you’re a woman talking to a man, than when you’re a man talking to a woman.)

It is still widely accepted to make fun of unattractive male archetypes, e.g. nerds, neckbeards, mouthbreathers, etc., but it’s very much not done to make fun of unattractive female archetypes, such as women who are overweight, anxious, clingy, ‘crazy’, etc.

It’s well-known that women’s suffering (e.g. in news stories, in charity advertisements, and so forth) drums up far more attention, care, and sympathy, than men’s suffering.

Explicit, unambiguous misogynist (meaning: literally woman-hating) statements are nowadays the domain solely of sleazy anonymous forums, but few modern men have not heard “men are trash” spoken by a woman, and not stopped, within a modern, public, progressive context. There is much, much vitriol against men in many progressive spaces; more explicitly toxic than anything I’ve seen directed at women in modern spaces that were viewed as even half as respectable.

It’s still very common and accepted, even in many progressive circles, to insult men by questioning their masculinity. Men being called manbabies, being told they’re fragile and their tears taste delicious, being told their actions are proof they’re compensating for a small penis, being accused of being bad in bed, being mocked when broken up with by their wives, being denigrated for never having had sex, etc. Even men’s looks are fair game in a way they aren’t for women; male public figures regularly have their looks or their ways of physically expressing themselves, insulted. All of these are viewed as generally accepted ways to attack men. Women face these sorts of insults dramatically less in any remotely respected space. You’d have to look hard to find a public intellectual say of some female politician that she’s an old hag, that her pussy stinks, and so forth; meanwhile, equivalent insults against men are a dime a dozen.

Dating apps straight-up murder men’s self-esteem. Regardless of how real-world attraction works, attraction on dating apps is based on forms of data that work for women looking to be attractive (e.g. a large focus on photos) but which do not work well at all for men, giving many men a profoundly negative impression of their actual attractiveness and value as a person. Online dating culture is infamously unequal, with the Gini coefficient of the ‘Tinder economy’ being worse than that of 95% of global economies. The hit to many men’s self-esteem is incredibly high; meanwhile, even average women’s self-esteem benefits greatly from often being easily able to rack up hundreds of likes on dating apps.

When women are weak and falling apart, there’s a cultural expectation placed on men (e.g. their husbands) to catch them and support them; but when men are weak, there is far less such cultural expectation placed on anyone. Men simply receive less support from those around them.

Insofar as women’s attractiveness lies in their looks and their mannerisms, and men’s attractiveness lies in common knowledge of social validation from others, as well as their communal standing, modernity’s increased atomization (read: the dissolution of the bonds within and between cultures) and globalism (read: the increased diminishing of long-term communal bonds, communal shared knowledge; and a greater reliance on having to signal your worth within short-term, low-information contexts; and so forth) have made it much harder for men to be attractive to women. Many of the usual ways in which women would usually find men attractive, are unavailable to men now.

There is much cultural sympathy for ‘fragile femininity’, i.e. when women feel insecure about their own femininity. (For example, when women feel like their bodies do not fit society’s notions of femininity, said notions are simply expanded to include them.) Meanwhile, when men suffer from fragile masculinity — and men do genuinely suffer from this; they experience real pain from many aspects of what people call fragile masculinity — then this pain, their suffering, gets laughed at, held up as proof that these men are weak and unmanly and undignified and deserve to be made fun of rather than be sympathized with.

In dating, when it comes to physical attractiveness, women get derided for being overweight, which they can change, whereas men get derided for being short, which they cannot change.

On the topic of actual inter-gender hatred: Men who hate women, still want women; they just often have a model for how women should be and behave, demands for things women should accept (e.g. these men themselves, romantically), that the majority of women simply absolutely don’t want to accede to. Women who hate men, meanwhile, often don’t seem to have any model for things men could do to be acceptable in their eyes; they just straight-up hate (cis) men, and want to see us wholly removed from as many spaces and positions of power as possible. Both forms of hatred are awful, but the latter seems worse to me.

It is disheartening that a primary feature of men’s attractiveness is confidence; it strengthens men’s experiential belief that they simply cannot afford to show any weakness, vulnerability, or insecurity to the outside world.

As a result of the above, many men internalize such a great disdain for weakness, that they fail to recognize it in themselves, making them less capable of righting their own course when this is needed, of recognizing when it is their responsibility to mend relationships, and so forth. Weakness and failure are regular, everyday parts of reality; we are all imperfect and we all make mistakes. This can be completely fine, so long as you know how to gracefully live with your own imperfection. The cultural messages men are faced with make it much harder to do this, which robs many men of incredibly valuable relationship and life skills.

It is exasperatingly cruel that having less confidence makes men less attractive, as this makes many men even less confident, which makes them even less attractive, and so forth. I’ve seen many men fall victim to this negative spiral.

When men physically hurt women, it is viewed as outrageous. Meanwhile, when men physically hurt men, it is not viewed as being nearly as outrageous at all. Even when the violence is widespread or quite extreme, it’s not something people get outraged about. There’s a sense that men hurting men is localized violence, violence that takes place within the single entity of ‘men’, rather than violence that crosses the boundary from one entity (‘men’) to another (‘women’). We’re all simply people; men hurting men is individual people hurting individual people, and men hurting women is individual people hurting individual people; yet the latter is viewed as inherently more violative than the former.

One might frame women’s social strategy when having problems as being to share, listen, and socially support one another through them, to validate and reassure each other that one’s inherent value is safe, that it is separate from what happens externally, that one need not bear responsibility or take action; this strategy is implicitly based in a belief that one has little agency. Men’s social strategy when having problems, meanwhile, may be framed as being to share practical tips, to take action, to solve problems in the external world; this strategy is implicitly based in a belief that one has much agency. In many modern cultures, women often complain when they share problems only for men to offer practical advice instead of giving space, attention, and validation; this cultural mis-match is often blamed on men, who are told to recognize that this is not what women wanted.

Using the same model of gendered problem-resolving strategies, but with a framing incompatible with the point made above: when men complain about their suffering (e.g. in dating), both men and women often give them practical advice, when often what these men really want and need is for someone to sit with them, to witness them in their pain, to listen to them, give them space, attention, love. It’s easy for practical advice to arrive as though saying, “get your problems out of here already.” Often this is the only messaging men receive when they are in pain. It can be hurtful for men who read not masculine but feminine problem-solving as love, to see women receive this love very frequently, but men almost never.

Continuing with the above framing: it can very easily seem like, and indeed often is the case that, attractive women receive more support when their attractiveness harms them, than unattractive men get when their unattractiveness harms them.

In dating, it feels more secure to know you were chosen (which more women are) than merely accepted (which more men are).

Unattractive women are in society invisible; unattractive men are in society ridiculed and viewed as a threat. The latter is worse.

There are many large and, to some extent, successful movements to help women feel less insecure about their bodies (which is among women’s greatest sources of insecurity and competition), but there are next to no movements to help men feel less insecure about their achievements and capabilities (which are among men’s greatest sources of insecurity and competition).