Three Hundred Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man — Introduction

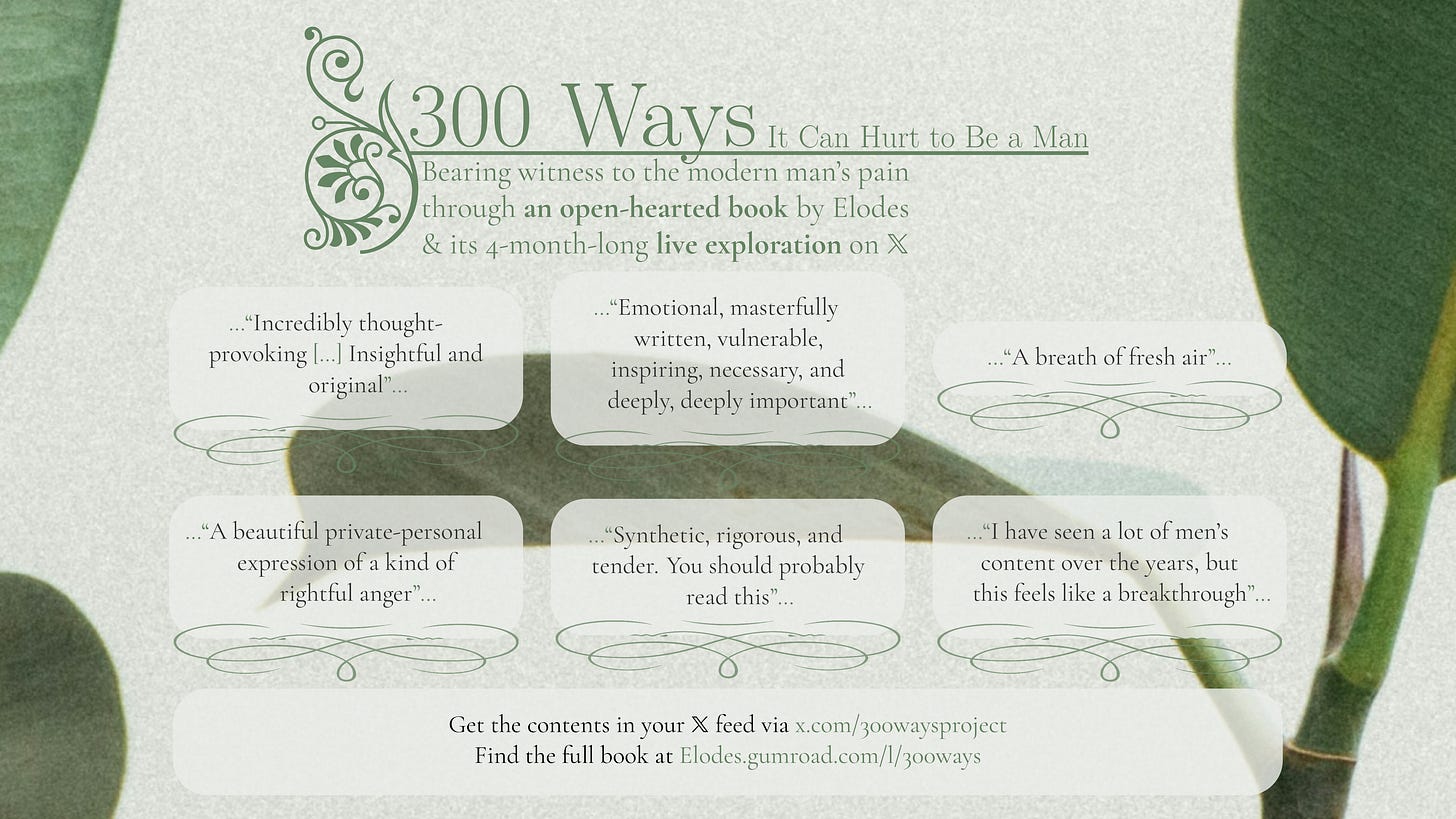

This Substack series has been made obsolete by its revised edition, 300 Ways It Can Hurt to Be a Man.

Available now as a book on Gumroad: https://elodes.gumroad.com/l/300ways

Get the contents in your X feed via x.com/300waysproject

————・𖥸・————

This series of posts is about sexism against men.

My own history is that as a not effeminate but certainly psychologically feminine teenaged boy, and well into adulthood (indeed up to this day), I felt I suffered in many ways from being male. I also felt that the ways in which I suffered were obvious. I thought it was clear to everyone that it was surely better to be female; that women have it easier and better. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was in desperate need for a community, a culture, where my suffering could be made legible, where people older and wiser and more knowledgeable than me would help me see, articulate, and resolve the problems I, being a man, faced.

(Many of these problems, by the way, were caused by internalized misandry, parts of which still remain. The story of how I am resolving this, I save for another day.)

I soon entered college, and there was introduced to a very feminist culture. These were genuinely good people, or at least people who genuinely tried to be and do good, and I related to their disapproval of many masculine ways (of being, of interacting, of speaking, of behaving), their fervent belief that there are other, better ways of existing and inter-existing. Most of all, I felt enamoured by the notion of a community that understood the difficulties that gender and gender roles and norms can bring. Here were people who spoke with great authority and great confidence about these things; surely, I thought, this would be the place for me. I joined in and participated in (read: I shut up and, as men were often implicitly and sometimes explicitly requested to do, listened to) their discussions, their queer festivals, their poetry slams, their vagina monologues, their women’s weeks, and so forth. I read some Woolf, some Butler, some hooks, and some Paglia (though less of her than I’d like, I’m sure).

One event in this journey stands out to me the most. During one such women’s week, the local feminist community figured that amidst events centered around women, they’d also host a discussion on male issues. I joined, of course, but it quickly became apparent that every single woman who spoke there (and perhaps every single man who did not, though as I was one of them I am less sure of this), simply had no clue what sorts of problems men could face. That doesn’t mean they were bullshitting or anything; they just couldn’t come up with much at all to discuss, and were generally unable to keep the conversation alive. I say this not to be mean; I really did appreciate their attempt. But this was the moment when it started to dawn on me that despite their authoritativeness, their great knowledge, their loudness and their confidence, their books and talks and discussions, and most of all their focus on empathy, on listening, on understanding — despite all these things, these problems I had as a man, which I thought were surely so obvious that everyone could see them and were just choosing to ignore in favour of women’s problems, were in fact genuinely invisible to nearly everyone.

Over time, it became clear that by and large many of the women and men in these communities, on top of disliking masculinity, held little respect and love for men as well. I’ve seen many otherwise kind and intelligent women and men (and queer folks, too) assert a great disdain and sometimes even disgust, not just for masculine men (which would be bad in itself), but also for e.g. nerdy or otherwise non-masculine men; and men’s considerations, preferences, and needs were usually entirely absent from any conversation. During this time I developed a deep shame around being male on top of my existing internalized misandry. I felt very betrayed once I realized that this was happening; the culture which was sold to me as being a safe home for femininity instead turned out to mostly care about women, behavioral traits be damned, and was often all too happy to throw men under the bus. This culture loudly advertised itself as believing in equality, but their actual beliefs and actions suggested a model where men and women are viewed as equal solely on the level of nature. As far as nurture went, meanwhile, it was widely accepted that men — not intrinsically enough for it to be biological, but certainly generally and deeply enough for it to affect every man you’d ever want to say this about — simply have a bad culture that causes them to do things like be violent and hurtful and inconsiderate and treat women badly, and that this culture was in fact so deeply embedded in men that it couldn’t be improved, but had to be wholesale destroyed.

I want to be clear here: I think the majority of people I met in these communities were good, likable people, possessed of many qualities which recommend them. Their problem, as far as I’m concerned, was that they were working within a deeply incomplete frame. A primary implicit and often explicit belief in many of these communities that I’ve come across, is that men face very few problems of their own, or wherever they might, that said problems are solely side-effects of yet greater forms of sexism against women. The end result is a culture that sometimes paid lip service to the existence of male suffering, but which never meaningfully acknowledged or tried to resolve it.

Frankly: that sucks. It sucks because men’s suffering is very, very real. It sucks because men’s suffering is widespread; in closed spaces and whispers, many men echo my suffering. And it sucks because these cultures and communities are actively and intentionally claiming and soaking up discussion space around gender, making it harder and harder for any man to come out and talk about the problems that they face specifically as men. A man nowadays can barely talk openly about his own pain, his own problems, without being viewed as intentionally distracting from women’s suffering. In particular, a man can barely mention pain borne from women’s actions, without being made out to be a misogynist asshole.

But I can’t not speak about these things. Thus I will speak about them.

There are a number of titles that this list does not have. It is easy to make the mistake of thinking this piece does in fact have one of those titles. However, it does not. Those titles include the following:

300 Privileges Women Have. Not every woman benefits from the things listed here; and even those who do, do not benefit from all or even many of them. Indeed, many of the claims I make here directly imply a symmetrical claim about why it can suck to be a woman. Moreover, the term ‘privilege’ has accusatory vibes, and I am not here to blame, shame, or guilt people.

300 Things Women Can Be Grateful For. This feels nicer already, and since it has come to my attention that many women have very little sense at all for why they might feel grateful for their being female, one wonders if they might not be aided by a list of things they may be grateful for. Ultimately however I am not a woman and thus I am not the right person to speak to women about ways they could better enjoy their lives. This task I leave to the wonderful women in my life, and those outside of it.

300 Reasons Men Have It Harder. This title implies men have it harder than women. Though many of my points take the form of “life for men seems harder in this particular way than life for women,” I make no claims as to who has it harder overall.

300 Reasons Why It Hurts To Be A Man. This title implies that all listed reasons are valid for every man. This is not the case. I can imagine men for whom the majority of items on this list do not hold.

300 Potential Qualities of Being A Man. This title implies that the things mentioned are all just a matter of perspective. For what it’s worth, I do think some of them represent tradeoffs: we lose a little, we win a little. Thus a neutral framing might make partial sense, at least. Ultimately, however, I have chosen a negative framing, 1) because I think many of my points represent genuine negative qualities of being male, 2) because this piece is intended primarily for me to express the ways I’ve personally suffered, not benefited, from being a man, and 3) to extend a helping hand most of all to those men who resonate with my experiences. An olive branch, meanwhile, to those who thus far have denied that any man could.

Point (3) is crucial to understanding this piece. I know it is difficult to imagine the author of a post named “Three Hundred Ways It Can Hurt To Be A Man” has any point other than “Men have it harder than women,” but in fact I really do not mean to say that men have it harder than women. I am sharing 300 ways it can hurt to be a man; in order to turn this into the conclusion that men have it harder than women, you would first need to prove that there could not exist a list of 300 equivalent or equally weighty ways it can hurt to be a woman.

(Such a list does indeed exist.)

If you’re a man reading this post: I trust it speaks for itself.

If you’re a woman and you’re wondering how to relate to this post, I invite you most of all to keep in mind that X being bad in no way precludes the opposite of X from also being bad.

Let me give a brief example where this is unintuitive for many men but quite intuitive for many women, so you can better see what I’m getting at. Many men who have a hard time getting sex, envy women for being much better able to get sex, and in this frequently miss the ways in which sex being easily accessible can be a disadvantage for women, such as:

It’s easy to use sex as a way to pursue validation or love, which can be unhealthy and damaging since there are many women for whom this actually gives them very little of what they want and much of what they don’t want.

The bottleneck between many men and sex they like is access to willing women, whereas the bottleneck between many women and sex they like is more likely to be things like their own skill at setting boundaries and owning their desires, as well as reliably finding men they can trust without risking coming across men they can’t. Thus women don’t gain nearly as much sex they like, from simply getting increased access to willing partners, as men would.

Within a culture where slutty women are viewed negatively, having the option as a woman to be slutty is much less valuable than this same option would be for men.

An increase in women giving men sex quickly and easily, can shape cultural expectations telling men that when a woman needs more than one or two dates before she feels ready to have sex with them, she’s being weird or is just stringing them along, expectations which thus cause harm even to women who don’t use the option of easily accessible sex.

…and so forth.

In much this same way, there may be many archetypically masculine traits or values which you might be used to viewing as strictly positive or beneficial to men (such as increased belief in their own agency, being respected for their capabilities and personality rather than for their looks, being more physically powerful, and so forth), which I will be discussing the many negative sides of. (Nested within this is, of course, the mirror notion that many archetypically feminine traits, roles, and expectations, may in fact be valuable and desirable.) I hope you will be open to this.

Finally, I’d like to clarify that I’m not here to guilt or shame women. I do think women play an important and often crucial role in many of the negative dynamics I describe in this post; I do think many women could do much better; and I am angry at the way so many women seem profoundly unwilling to accept and confront men’s pain, even as they fight to heal women’s. But while I know the culture and wish it would change, I do not know you, so it is not my place to tell you to do better. The type of woman who would seek to support and empower men, I trust will find her way to this better without guilt or shame blocking her along this path. I hope she feels welcome here, and that she will view my statements not as demands to change, but rather as invitations which she may say no to wherever she feels this would be wiser. The type of woman who would not seek to support and empower men, meanwhile, is welcome too; it is not required to do this particular type of good, in order to be a good person. The type of woman, however, who would seek to work against men, would not listen to me either way. Thus I have nothing to say to her, and she should feel called to leave.

In the end, I can write down for you rules that I wish you’d follow, but out in the real world, the rules will fail both of us time and again; only a genuine, fully integrated well-wishing love suffices. It is said that when love is lost, there is the law. I can give you my version of the law, but no power in the world could let me force your love. I may only trust it is there, and, in acting, find out. I hope you too, reader, can yet put a similar trust in me.

[Continue to the Index for an overview of posts in this series.]

This is landmark Men’s Issues writing.